The Election of 1912 was weird. It featured a former two-term president running under a newly formed third party because he was dissatisfied with his old one, a candidate who had only recently won his first political race, a socialist seeking significant gains, and the incumbent president. In many ways, it’s unique in American history. Sure, elections have seen three candidates all garnering a considerable amount of votes, but four candidates? No, only the election of 1912 holds that distinction.

The story of the 1912 election really begins with the 1908 election. President Theodore Roosevelt decided not to run for a third consecutive term. Instead, he threw his support behind his friend and fellow Republican William Taft. Taft was a lawyer by trade and had spent time as a Judge in an appeals court. His ultimate dream was likely to be nominated to the Supreme Court.[1] However, after serving as Secretary of War under Roosevelt, Taft found himself the Republican candidate for 1908.

Roosevelt likely supported Taft because he saw a friend who would follow in his footsteps. But where Roosevelt thrived as president, Taft struggled.[2] Reading about Taft’s time as president, it becomes clear that he was uncomfortable in the role. He genuinely seemed depressed to be the president.

Lacking Roosevelt’s charisma and love of the presidency would not have been enough to drive a wedge between the two men. However, Taft’s turn away from Roosevelt’s policies was a different matter. First, Taft replaced the Roosevelt cabinet even though he had indicated he would keep Roosevelt’s men.[3] Then Taft fired Chief Forester Gifford Pinochet. Pinochet was a conservationist and the first Roosevelt’s plan to protect America’s land.[4]

There was also a personal element to the Roosevelt/Taft split. After winning the election, Taft wrote a letter to Roosevelt in which he credited his brother Charlie and Roosevelt for his victory. Charlie Taft had been the major source of funds for Taft’s campaign.[5] Roosevelt apparently did not take kindly to Taft splitting credit. Roosevelt said crediting Charlie Taft with the election would be like crediting Jay Cooke with saving the Union.[6] Roosevelt’s feelings were hurt. Poor guy.

If you don’t know about Jay Cooke, you can read a bit about him here.

If Taft had only annoyed Roosevelt, there might not have been a split in the Republican party. But Taft was annoying some of his fellow Republicans as well. In 1909, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff was up for debate among Republicans. The more conservative protectionist Republicans supported the bill, while the progressive Republicans opposed it. Taft ultimately sided with the bill, which put him at odds with the progressives.[7]

Roosevelt played it coy during the years between elections. He refused to break entirely with Taft, but he made sure to keep himself in the public eye. Like Jay Leno and the Tonight Show, Roosevelt was waiting to pounce. Sadly for Taft, his own mistakes and Republican missteps gave Roosevelt the opportunity.

The midterm elections of 1910 went very poorly for Republicans. They suffered defeats in major markets and lost the House for the first time since 1894.[8] It was a sign the president was weak. Then, in 1911, Taft sued U.S. Steel, claiming their 1907 acquisition of the Tennessee Iron and Coal Company was illegal. The problem with the suit is that it would mean Roosevelt was complicit in signing off on something illegal. Roosevelt was not pleased. At all.[9]

The die was cast, and Roosevelt was challenging Taft. On Roosevelt’s side were the progressive Republicans looking to keep the momentum of change, and on Taft’s side were the more conservative Republicans. The two Republican candidates entered the primaries with different strategies. Roosevelt wanted to lean on his popularity and charisma. Taft used his knowledge and power within the Republican Party. Roosevelt had more votes than Taft by a significant margin, but Taft won the nomination due to his political machinations.[10]

How did Taft win with fewer votes? Well, while Roosevelt had close to 400,000 more votes than Taft, there were a number of delegates in dispute, 254 of them to be exact. The winner of the contested delegates would win the nomination, and it was up to the Republican National Committee to decide who won each delegate. The committee was staffed mainly by Taft supporters. You can see where this is going. They gave the contested delegates to Taft, essentially giving him the nomination.[11]

I don’t know if Roosevelt would have run as a third-party candidate if he had lost in a more fair manner. However, feeling that the election had been stolen from him, and with at least some justification behind those feelings, Roosevelt decided to form the Bull Moose Party. The Bull Moose Party would draw from the most progressive Republicans who fit the Rooseveltian way. It was also a really cool name for a political party.

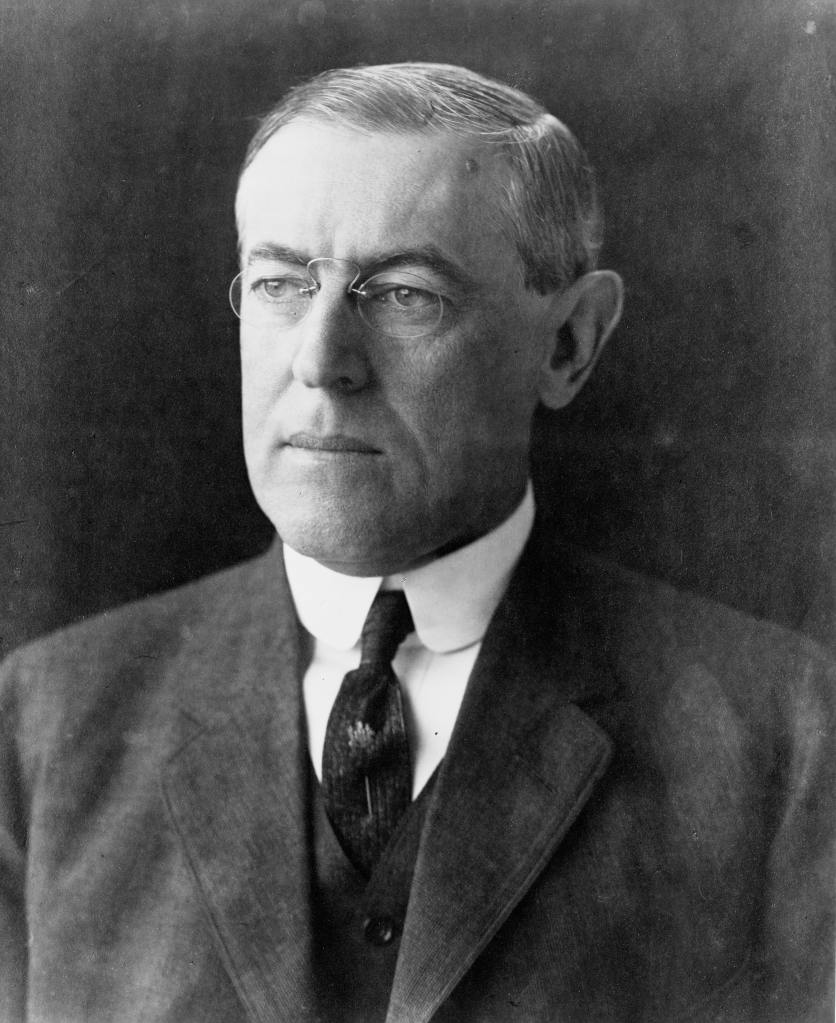

So that’s two candidates out of the way. Let’s move on to the third, Woodrow Wilson. At the time of the election, Wilson was serving as governor of New Jersey. He had recently won the position in 1910 after previously serving as the president of Princeton University. Wilson was also a bit of a progressive and fought hard to reform the Democratic Party away from the old political bosses.

Wilson was not the front-runner during the primaries. The Speaker of the House, Champ Clark from Missouri, was the leading candidate. However, the Democrats followed in the Republicans’ footsteps and had their own political shenanigans. When the delegates were counted, no candidate could reach the required two-thirds majority. Party leaders began discussing potential deals and delegate trades behind the scenes. The result was that on the 46th ballot, Wilson won the election when his side made a deal to keep 100 potential delegates from voting for Clark.[12] Politics is ugly. Also, I’m upset that we could have had a president with the nickname Champ and blew it.

Before moving on, I would like to bring to your attention an anecdote that historian James Chace was kind enough to include in his book. Chace describes a letter Wilson wrote to his wife, in which he expressed his fear of staying in New York due to his “mysterious passions” and what he might do.[13] Wilson was a weird guy.

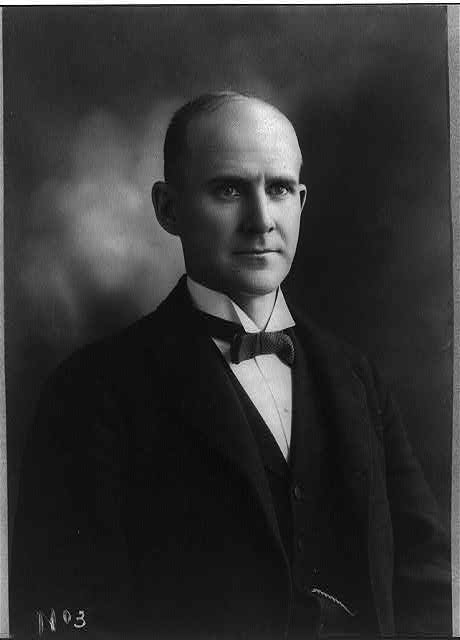

The final of the four candidates was Eugene V. Debs. Debs was a one-time railway union leader who spent time in jail for his role in the Pullman Strike. The Pullman Strike was a nationwide railway strike that eventually required government intervention. After serving time in prison, Debs converted to socialism.

Debs ran for president in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920. His 1908 and 1920 races are particularly memorable. In 1908, the Socialist Party chartered a train nicknamed “The Red Special,” which toured the country. Debs only received 420,793 out of 14 million, but it caught people’s attention.[14]

Debs was actually in prison in 1920 for violating the Espionage Act. His slogan was “From the Jail House to the White House.” Yet, despite having a limited ability to reach voters, he received just under a million votes.[15] Debs’ story is fascinating, but now it’s time to move on to his best election in terms of voter percentage, 1912.

The election of 1912 featured the establishment Republican, the Progressive Republican, the anti-establishment Democrat, and the Socialist. Roosevelt ran under the banner of “New Nationalism.” The New Nationalism platform advocated for a larger, more active government. The Federal government would heavily regulate businesses and favor labor over corporations. It would also take on the moral imperative and fight for justice and equality.

Wilson ran under the platform of “New Freedom.” Wilson advocated for the need to control monopolies. He planned to use regulation to limit monopolies, thereby increasing competition and benefiting the economy. However, where Wilson deviated from Roosevelt was the plan for the government outside of monopolies. Wilson wanted to shrink the overall size of the government. He wasn’t looking to regulate every aspect of business. More importantly, Wilson saw no need for the government to fight for equality and social change. If you know anything about Wilson, you know that’s not shocking at all.

Debs was a socialist, so he ran under the ideals of socialism. He sought government control over industry and advocated for strong, union-based labor laws. He was, in fact, a slightly more extreme version of Roosevelt. Debs viewed the world through its class structure, so fixing that would help address social issues.

Taft was the sitting president. He ran on a platform of maintaining the status quo. This platform isn’t uncommon for sitting presidents. Why would you run on a platform of great change from what you’re doing? If what you’re doing needs to be changed, then so do you.

Historian James Chace said it best when he wrote, “For Roosevelt calling for a “New Nationalism,” the role of government was to regulate big business, which was surely here to stay. For Wilson’s “New Freedom,” the government’s task was to restore competition in a world dominated by technology and mass markets that crushed small business. For Debs, America needed federal control of basic industries and a broad-based trade union. As for Taft, the White House simply needed to apply the laws that were designed to restrain the excess of industrial capitalism.“[16]

The most spectacular moment of the campaign season was the shooting of Roosevelt. The scene was spectacularly described by Chace in his book 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debts- the Election that Changed the Country. This book is the source I used for the scene I described below.

On the afternoon of October 14, Roosevelt was leaving his hotel on his way to a speech. A large group of people was outside Roosevelt’s hotel. He was approached by a man named John Schrank, who pulled out a revolver and shot him. Roosevelt’s security quickly subdued Schrank. Roosevelt actually asked Schrank why he did it and told the audience not to hurt the man. Roosevelt, ever the determined figure, decided to proceed with his speech. After giving his speech, he went to the hospital, where doctors discovered the bullet had barely missed his heart.

Doctors told Roosevelt he needed to rest while he recovered. Roosevelt’s opponents all canceled their campaign events while Roosevelt was on the mend. I can’t imagine such respect being shown nowadays. Luckily for the other candidates, Roosevelt decided he only needed a week to heal and was back on the campaign trail by the end of October. The man just kept on going. Quick note: Schrank claimed that he had a dream in which President McKinley told him he needed to kill Roosevelt. So yeah, he went to an asylum.[17]

The rest of the campaign season ran as expected. The four men waited anxiously on election night, wondering what would happen. Would the expected split of Republicans propel Wilson to the White House? Would radical voters want Debs or Roosevelt? Would anyone else realize that Bull Moose was a really cool party name? Then came the results.

First, let’s look at the Electoral College, which was a landslide, with Wilson receiving 435 electoral votes to Roosevelt’s 88 and Taft’s 8. Debs received no electoral votes. The popular vote counts still gave Wilson the heavy majority with 6,293,454 votes (42%). Roosevelt came in second with 4,122,721 (28%). Followed by Taft with 3,486,242 (24%) and Debs with 901,551 (6%).[18]

Wilson clearly benefited from the split between Roosevelt and Taft. If you add their two vote totals together, they would win the election. However, historian Lewis Gould does not believe in that narrative. He wrote, “Pitting Wilson against Roosevelt in an imaginary match-up would have probably been closer, but the Democrat would have had the advantage. Disgruntled Republicans likely would have stayed home if Roosevelt headed the ticket.“[19] Gould argues that the split in the party would hurt the election either way, even if the awesome Bull Moose Party did not exist. The only thing I want to point out is that Gould doesn’t discuss what would have happened if Roosevelt had never decided to run and fully supported Taft. Or what happens if Taft doesn’t run for reelection in favor of Roosevelt? Both events may stop the split of the Republican Party.

For Debs, 1912 was his most successful election. He received slightly more popular votes in 1920, but in 1912, he received 6% of the vote, whereas in 1920, he only received 3%. The Debs-Roosevelt relationship is interesting to explore. Roosevelt was considered fairly radical and likely had the hearts and minds of voters looking for significant change. However, Debs was even more radical with his socialist agenda. It’s difficult to determine who stole voters from whom. As interesting as it would be to see Roosevelt’s vote totals without Debs, it’s even more interesting to think about Debs’ totals without Roosevelt.

And thus, America ended up with Woodrow Wilson as president. Joy.

[1] James Chace, 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs- the Election That Changed the Country (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 23.

[2] Chace, 11.

[3] Chace, 26.

[4] Chace, 14.

[5] Lewis L. Gould, Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2008), 23.

[6] Gould, 23.

[7] Gould, 33.

[8] Gould, 46.

[9] Andrew C. Pavord, “The Gamble for Power: Theodore Roosevelt’s Decision to Run for the Presidency in 1912,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 26, no. 3 (1996): 633, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27551622.

[10] Pavord 643.

[11] Gould, 105-07.

[12] Robert Dallek, “Woodrow Wilson, Politician,” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 15, no. 4 (1991): 111, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40258177.

[13] Chace, 46.

[14] J. Robert Constantine, “Eugene V. Debs: An American Paradox,” Monthly Labor Review 114, no. 8 (1991): 31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41843621.

[15] Constantine 31-32.

[16] Chace, 7.

[17] Chace, 231-35.

[18] Gould, 248.

[19] Gould, 253.

Leave a reply to Scott George Cancel reply