The Quakers in America are often a forgotten group. When they are remembered, it is for a commercialized version of their people that sells oatmeal. The truth is they were vital in the formation of the colonies and early America. They were critical figures in forming New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. They were pioneers of religious freedom and abolition. They were also pacifists. And in a time of war, pacifism is not a well-liked belief. As a result, patriots distrusted, shamed, and abused Quakers. The Continental Congress persecuted the Quakers in ways at odds with the concept of liberty. The revolutionary war was a dark period for Quakers.

The Quaker denomination began in England in the 1650s, and others immediately disliked them. Historian Hilary Hinds notes, “At the time of their inception in the 1650s, however, their reputation was less benign. Early Friends were seen by more orthodox believers as at best misguided and at worst evil.”[1] The dislike was due to the Quakers going to an extreme that most did not believe during the Reformation. They rejected many basic tenants of the Christian faith, such as Baptism, the Trinity, and all sacraments and ceremonies.[2] They were loose in their practices, like having church in houses and barns. They allowed attendees to speak out during the middle of the ceremony.

Like so many others, Quakers sought religious freedom in the New World. Unfortunately, they did not have much better luck at the beginning of their time in the colonies. In 1656, Boston returned two ships bearing Quakers back to their original ports. The reason Boston returned these ships was simply because they were carrying Quakers. Massachusetts made it illegal for Quakers to enter the colony. The most infamous case regarding this law is the hanging of Mary Dyer, which occurred on May 21, 1660. Mary’s only crime was continuing to enter Massachusetts.[3]

Realizing they needed their own space, the Quakers looked at the vast open landscape of the New World and founded their own colonies in Pennsylvania and Delaware. They also formed the backbone of New Jersey development in what was called the “West Jersey Province.” The Quakers were instrumental in growing these colonies that would play crucial roles in the American Revolution.

Before going further, the relationship between Quakers and pacifism must be discussed. Beginning with the Peace Testimony in 1660, the Quakers established they would not participate in war. The Quakers carried this belief with them across the Atlantic into the colonies. Puritans used it against them almost immediately. Historian Meredith Weddle notes, “Within Plymouth’s 1658 Quaker law was the provision that all those opposed to military service were disenfranchised, again evidence that Quaker opposition to training was well known to the Plymouth court two years before the Restoration.”[4]

The issue of pacifism would continue to surround the Quakers until it came to a head once more during the French and Indian War. The start of the war split the Quakers into two factions those who would adhere to the policy of peace and those who would take needed defensive measures. However, the more significant issue was the backlash the Quakers felt from others. Their refusal to contribute to the war effort made them an enemy in many eyes. Historians have noted that pacifism cost them their political power in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.[5]

Pacifism impacted the Quakers from the start. It was a factor in their removal from certain colonies and cost them long-standing political power. The breakout of war is the worst event for Quakers, from a moral standpoint and a political one. The Quakers could have predicted the events of the Revolution based on the past alone.

The breakout of war in America placed the Quakers in an awkward spot. First, the Quakers held close ties with England through their personal and business relationships. Worse, the Quakers feared that any change in government could lead to their persecution. They believed that their relationship with England protected their charter and saved them from the type of persecution they experienced by the Puritans. England was their tough best friend protecting them from bullies, and the American patriots were asking the Quakers to punch that best friend in the face—usually not a good idea.

The Quakers were forced to take several steps because of their belief that the Revolution violated their Peace Testimony and put them in a precarious position regarding their rights. First, they attempted to negotiate peace between the two sides. They leveraged their English brethren to accomplish this task. Clearly, they had no success. They also forbid their congregations from aiding the efforts of the patriots. They were not to impede the patriots in their goals but were not allowed to render assistance.[6] Following the requirement to not assist the patriots, they forbid anyone from participating in the war. Patriots did not appreciate Quakers withholding aid and refusing to fight.

Quaker pacifism became an issue quickly after the outbreak of hostilities. Influential writer, Thomas Paine, dedicated an entire section of his appendix to Common Sense to the Quakers. In his writing, Paine addressed a 1776 pamphlet written by the Quakers calling for peace. He claimed the call to pacifism was a lie and not a truly held belief. He challenged them to reach out to the King of England and tell him he was committing the sin of bearing arms.[7] Quakers could likely feel Paine’s influence in the following years as the treatment of Quakers worsened.

So, we know that Quakers were pacifists who sought to keep peace with England. Now we need to address the treatment they received at the hands of their fellow colonists. The first and most obvious way was through the use of taxes and fines. All colonies had a law regarding military service. If one was not going to serve in the military, they must find a substitute and pay a fine. If the offender did not pay the fine, the state would seize their property.[8] These taxes disproportionally impacted the Quakers since the majority of their congregations would not fight. It should be noted that it was not just the patriots using taxes, fines, and seizures against the Quakers. The British forces undertook the same methods when they occupied Quaker land. There are numerous examples from occupied New York where the British levied taxes against the Quakers. When these war taxes went unpaid, the British fined the Quakers and seized property.[9]

Another way the patriot governments persecuted Quakers was with the Oath of Allegiance. The oath required citizens to swear a loath of fealty to their state and renounce any such fealty to England. As previously discussed, the Quakers were leery of separating from England and believed oaths such as these brought them into the conflict. Refusal to take the oath once again resulted in fines and property seizure. It also resulted in the inability to work at certain occupations like teaching. This occupation ban would result in the shutdown of many Quaker schools.[10] However, the punishment could be even more severe as patriots hung two Quaker men in Philadelphia for their refusal to swear the oath.[11]

When taxes, fines, and property seizures did not work, state governments went with more extreme measures. A favored method of punishment for Quakers refusing to cooperate was exile. There were several cases in New York where authorities exiled Quakers to British-controlled territories. However, the most famous case of exile occurred in Philadelphia.

In the Summer of 1777, the Continental Congress received a document claiming to have been obtained at the Quakers’ yearly meeting at Spanktown, NJ (Yes, this is a real place. It is now Rahway). This document listed several questions from the British to the Quakers about the current state of the Continental Army. Attached to this document were the responses from the Quakers addressed to the British Army. Congress was outraged, and it did not matter that this document was a complete forgery and no meeting took place.[12] Congress did not hesitate to respond to the letter, and on August 28, 1777, they passed a measure to arrest the Quakers they felt responsible for the seditious act. The names selected were entirely subjective, with no sound reasoning ever provided.

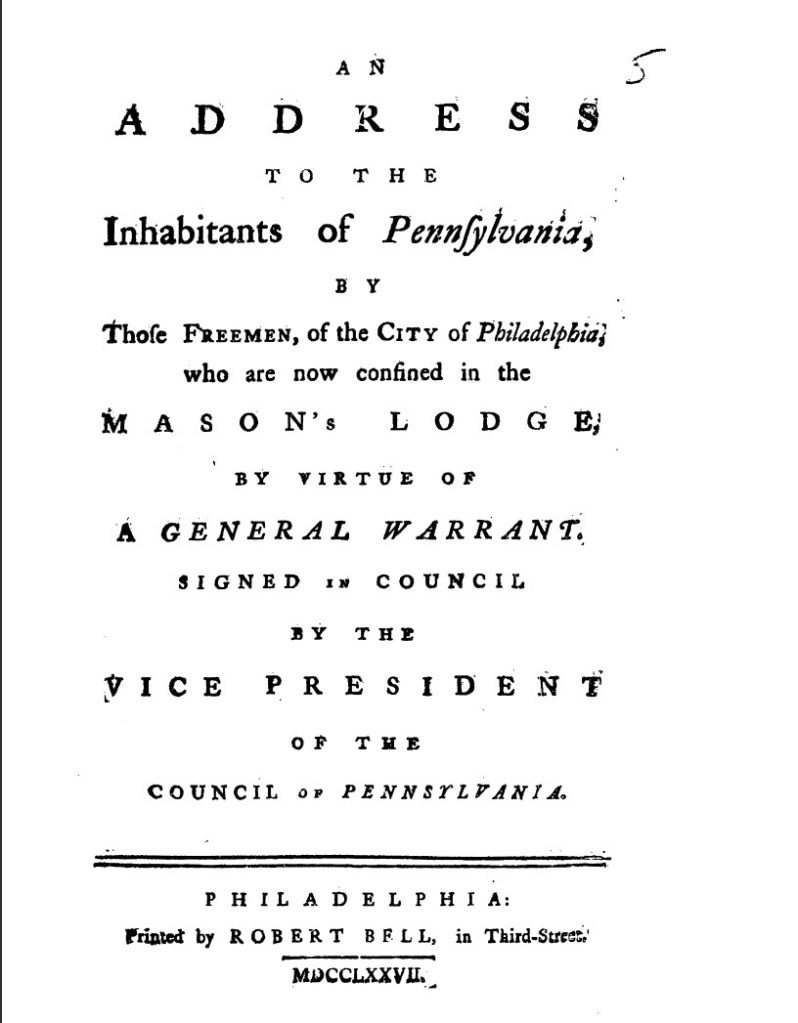

The government ended up arresting 41 Quakers, with 19 later released. Authorities held the remaining 22 Quakers in a local Masonic lodge awaiting exile to the Virginian frontier. This quick resolution and arrest were not borne out of the panic of traitors but likely the result of a long-standing dislike and distrust of Quakers. One of the most prominent American leaders pushing for punishment was John Adams. John Adams had long held an aversion toward Quakers. Adams had numerous personal clashes with the Quakers over the years, especially with one of their leaders Isaac Pemberton. Historian Arthur Scherr described the impact of a confrontation between Adams and Quakers from 1774, “In Adams’s draft autobiography, written in 1804 –1805, his encounter with the Quakers looms large. Rage at their lack of deference toward him incubated in his mind. Apparently, Adams never forgave Pemberton’s actions.”[13] The terrible deed committed by Quakers towards Adams? It was setting up meetings to harass him about Massachusetts persecuting Baptists.

Adams was heavily influential in the decision to punish the Quakers. He was assigned a position on the commission to determine what actions Congress should take toward the supposed traitors. Undoubtedly, he took this opportunity to punish them in the harshest terms he felt he could get passed through Congress. The imprisonment and exile of prominent Quaker leaders were not because of any actual threat they posed but instead in accordance with previous biases towards the denomination.

The Quaker prisoners only achieved freedom only by publishing a series of letters to the public. These letters spoke of their imprisonment in the same words used by the American government in its desire to separate from England. They used the phrases “liberty,” “rights of free men,” and “civil liberty” to frame their plight in the same light as the colonies.[14] These letters were effective, and public outcry was immense. The outcry led to the eventual release of the prisoner. It took an alignment of causes to gain the freedom they deserved.

The American people distrusted and disliked the Quakers at the time of the American Revolution for no reason other than their beliefs. Some patriots would use the loyalist tendencies as an excuse for their mistreatment, but it overlooks two vital facts. The first was that the Quakers had a valid reason for not wanting to separate from England. They feared for their religious liberty and worried about persecution. Their history in Massachusetts provides a strong foundation for this fear. Considering Congress removed the Quaker’s charter for Pennsylvania with the Declaration of Independence, the anxiety regarding their protections seems valid. Secondly, while initially, they wanted to remain with England, they never actively assisted the British. In the Revolution’s early days, they refused to assist rebels, but once war broke out, they removed themselves from all activities and simply existed.

Loyalist leanings were not the only reason patriots disliked the Quakers. Their belief in pacifism made them enemies even before the outset of the war, but once the Revolution began, that dislike amplified. Patriots either believed the pacifist claims to be a lie or just a ridiculous belief and punished the Quakers for them. The taxation, fines, and property seizures were all a result of Quakers not wanting to participate in a war. Beyond those measures, Quakers were exiled or even killed for their antiwar positions. The Continental Congress was happy to go along with the Quakers’ punishment based on a forged document they never verified.

Quakers built Pennsylvania and New Jersey into two of the strongest states in the American Union. They were responsible for the wealth and prosperity of the nation’s first capital. However, because their beliefs placed them on the outside of society, patriots were eager to forget these contributions and punish them when the time arose. It is an injustice of the American Revolution.

[1] Hilary Hinds, George Fox and Early Quaker Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 1.

[2] Sydney G. Fisher, The Quaker Colonies (Luton, Bedfordshire, UK: Andrews UK Ltd., 2012), 1. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=4460780.

[3] Anne G. Myles, “From Monster to Martyr: Re-Presenting Mary Dyer,” Early American Literature 36, no. 1 (2001): 7, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25057215.

[4] Meredith Baldwin Weddle, Walking in the Way of Peace: Quaker Pacifism in the Seventeenth Century (Oxford University Press, 2001), 93. https://doi.org/10.1093/019513138X.003.0003.

[5] Theodore Thayer, Israel Pemberton: King of the Quakers (Chicago, IL: Papamoa Press, 2018), 160-61. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/detail.action?docID=5843336.

[6] Arthur J. Mekeel, “The Relation of the Quakers to the American Revolution,” Quaker History 65, no. 1 (1976): 9-13, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41946787.

[7] Thomas Paine, “Appendix to Common Sense,” in Common Sense: With the Whole Appendix: The Address to the Quakers: Also, the Large Additions, ed. Thomas Paine, Cambridge Library Collection – Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 137-47.

[8] Mekeel, 15.

[9] Joseph John Crotty, “”Times of Peril”: Quakers in British-Occupied New York During the American Revolution, 1775-1783,” Quaker History 106, no. 2 (2017): 58-59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45180030.

[10] Mekeel, 16

[11] James Fritz, “Gathering Storm Clouds: The Pacifist Culture of York County, Pennsylvania, During the American Revolution,” Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 37, no. 3 (2014): 95, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=31h&AN=101456668&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=liberty&authtype=ip,shib.

[12] Paige L. Whidbee, “The Quaker Exiles: The Cause of Every Inhabitant,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 83, no. 1 (2016): 34-35, https://dx.doi.org/10.5325/pennhistory.83.1.0028.

[13] [13] Arthur Scherr, “John Adams Confronts Quakers and Baptists During the Revolution: A Paradox of the Quest for Liberty,” Article, Journal of Church & State 59, no. 2 (2017): 267, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jcs/csv119.

[14] An Address to the Inhabitants of Pennsylvania, by Those Freemen, of the City of Philadelphia, Who Are Now Confined in the Mason’s Lodge, by Virtue of a General Warrant. Signed in Council by the Vice-President of the Council of Pennsylvania, vol. 43330 (Bell, Robert, 1732-1784, printer., 1777), 1-36. https://docs.newsbank.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:EAIX&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=0F2F82C95B7AED68&svc_dat=Evans:eaidoc&req_dat=55C93F06388D4FEF907B19BE98D77468.

Leave a reply to Ozog Cancel reply