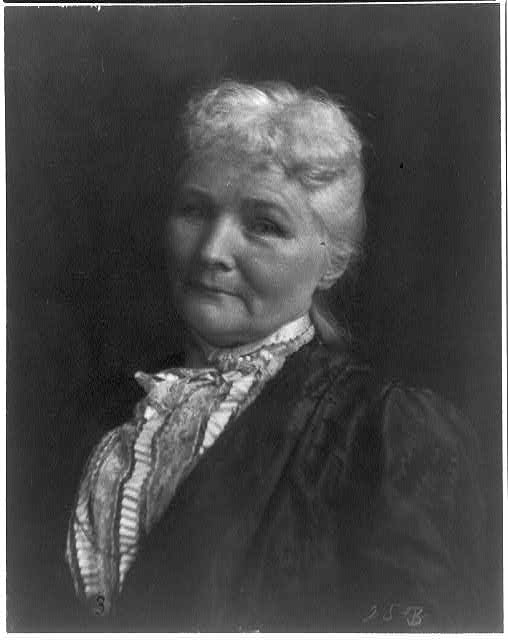

Labor battles in the history of the United States have not been without violence. Even though I understood that fact, I was shocked by the violence of the West Virginia Mine Wars between 1912 and 1921. I had not even heard of this fight before I randomly saw a mention of it in a book. Yet once I started reading, I was shocked. This story involves workers’ rights, machine guns, and mine accidents. The miners’ struggle touches parts of WWI. The story even features an 80-year-old woman called Mother Jones supporting the workers. How could I not have known about this? And yes, Mother Jones is THE Mother Jones that inspired the well-known magazine.

Workers may go on strike for better wages, benefits, working conditions, and hours, among other things. Miners in West Virginia in the early 1900s wanted all of these things for good reasons. They worked back-breaking days and got paid in company scrip that could only be used in company stores. These stores had prices far higher than stores owned by third parties.[1] The mining companies essentially made money twice off miners’ labor. I want to note that company scrip wasn’t just a West Virginia issue but a mining issue in general. The famous song Sixteen Tons was written about Kentucky mining, but discussed the same problem.

Miners had to live in company housing since the mining companies owned all the surrounding areas. You’d think this wouldn’t be the worst thing since it would save the miners from the cost of building their own homes, but in practice, it was terrible. Mining companies could evict a miner at will. And they did anytime they fired someone. At one point, West Virginia courts ruled that the relationship was not between landlord and tenants but between masters and servants.[2]

But hey, it’s no big deal, so you have to work long hours at a demanding job only to pay far more than other people for your groceries. And sure, you live in a house you can be kicked out of at any moment if you annoy your employer. It’s not like you work an extremely dangerous job. Oh, wait, being a miner in West Virginia was so dangerous that it had a higher proportional death rate than the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI.[3]

I think you can understand why the miners were primed to strike. They were treated terribly and constantly under the thumb of the mining operators. Their life was mining, and the operators loved it that way. Things had to change. Sadly, the mining companies would not let go of control easily, and the result of miners fighting for their rights was violence and death.

Before continuing, I want to provide some background on who the miners were in West Virginia. They came from different groups, such as Eastern Europeans, Italians, and African Americans. While families were prevalent throughout, mining contained a lot of young single men. They were hard drinkers and quick fighters.[4] Honestly, I think if I asked you to picture a West Virginia miner in 1912, you’d probably have the right portrait of the man, strong men who worked themselves to the bone in the mines.

The wives of the miners who did marry did not just stay at home. The wives built the coal communities. Organizing activities, teaching children, and taking jobs such as a seamstress when needed.[5] One prevailing theme I noticed when reading about the Mining Wars was that when the men went on strike, their wives were there with them. They kept things functioning when their husbands stopped earning pay. I’m not sure the strike lasts more than a few days without the wives.

The West Virginia miners attempted several strikes before 1912, but this article will not discuss them. I’m trying to be concise here, people! However, if you are interested, my two major sources for this article discuss the previous attempts. Please pick up a copy of James Green’s The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom and David Corbin’s Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners 1880-1922.

By 1912, American miners had realized they needed to unionize, so they formed the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The UMWA is the organization the West Virginia miners turned to when they realized they needed to push for change. In April 1912, representatives of the UMWA met with members of the Kanawha Coal Operators’ Association, whose miners worked in Paint Creek. They request the following: an eight-hour day, a pay increase of 5 cents per ton, to refrain from blacklisting union members, to install accurate scales in all mines, and guarantee free speech and peaceful assembly to miners. They felt these requests were reasonable because miners in other areas had just won these concessions.

Mine operators said no. They didn’t want to give a single concession to the men working their mines, even when the miners removed all their demands except a pay increase. The miners had no choice. They went on strike.

The operators would not sit idly by while workers cut into their profits. First, they hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency (similar to Pinkertons, which I covered here) to send agents to act as guards and strikebreakers. They then began evicting the miners’ leaders from their homes.[6] One such miner was Frank Keeny. Keeny was a socialist who ended up being the premier West Virginia mining union leader during this time.

When the strike continued to drag on, the operators decided to evict all striking miners from their homes using their personal police force, the Baldwin-Felts agents. There is even one story of agents evicting a miner and his wife as she was giving birth.[7] The evicted strikers moved to a tent town called Holly Grove.

I guess the operators and detectives thought moving the miners into tents would be enough to persuade them to change their minds. However, when the miners kept striking, the detectives decided to escalate things. One day, they decided to fire shots at the Holly Grove camp. No one was killed or injured.[8]

Miners, of course, would not just accept this with no response. On the morning of May 29, miners fired upon Baldwin-Felts agents eating breakfast. The agents were inside originally, but when they went outside to investigate the shots, the gunfire intensified. Again, no one was injured or killed.[9] I’m unsure if the agents and miners were Stormtroopers from Star Wars, but their aim leaves the question open for debate.

Loss of life cannot easily be avoided when gunfire is involved. On June 4, Baldwin-Felts agents moved to intercept strikers, planning a raid against a detective. The resulting gun battle left one young miner dead. It also led to the arrest of five miners.[10] It would not be the only killing committed by Baldwin-Felts agents. Hatred grew and intensified between the striking miners and the Baldwin-Felts agents. Corbin describes a story in which a train conductor carrying wounded miners and agents witnessed a miner spitting tobacco juice in the eyes of a dying agent, telling him he better die.[11] I know it’s a serious situation with a dying man, but that’s gross.

The operators may have had the Baldwin-Felts agents, but the miners had Mother Jones. Born Mary Harris Jones in Ireland, Mother Jones would become synonymous with labor battles in the United States. Jones would travel across the country, helping workers battling for better rights. She spoke at rallies, provided advice, and acted as a symbol of resistance. Jones had previously been in West Virginia in the early 1900s when miners tried to strike. Jones would lead protest marches in the West Virginia capital of Charleston. She would even use her friendship with a Democratic congressman to stage a protest in an armory in Washington, DC.[12]

Violence continued as operators refused to meet mining demands. The West Virginia governor, William Ellsworth Glasscock, declared martial law.[13] His successor, Henry Hatfield, would also declare martial law. Initially, the thought was that martial law would be applied evenly, with both sides disarming. However, in practice, martial law heavily favored the operators. The greatest miscarriage of justice was the military tribunals used only against the miners.[14]

The military arrested 200 miners and Mother Jones. The striking miners were accused of violence, leading to the death of a company clerk. With little evidence, the tribunals convicted all the people arrested. The military judges then gave out sentences ranging from 5 to 20 years. Mother Jones was sent to the state penitentiary for 3 years.[15]

The military could not keep their actions under wraps, and soon, news spread of the actions taking place in West Virginia. Mother Jones sent letters to influential politicians, including the Secretary of Labor, William B. Wilson, and Senator John Kern. Kern read a letter Jones wrote during a session of Congress.[16] This led to a Senate investigation and Mother Jones’s ultimate release from prison.

Violence continued for the next several months while deals reached the finish line, only to fumble. However, the mining companies and the miners eventually signed an agreement in 1913. The Senate investigation into the use of martial law had removed the possibility of it being used again in the near future. As a result, mine operators felt compelled to settle the strike since they lost their best weapon. They granted the original demands.[17]

The years following the first round of strikes were quite profitable for the mining companies. WWI started, and suddenly, there was an incredible increase in demand for coal. Things only got better for the mining companies when America entered the war. Suddenly, not working at certain levels was traitorous. Operators gained some of their old powers back under the guise of “patriotism.”[18] It didn’t help miners that much of their union leadership was socialist, which meant enemies of the United States. Another round of battles was about to begin.

This time around, instead of the violent battles being in Paint Creek, they would take place in Mingo, Logan, and McDowell counties. Union leaders Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney tried to send supporters into these counties in November 1919 to help the local miners organize. However, the organizers were unsuccessful, with rumors circulating that they were beaten and murdered. Somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 coal miners marched on Logan County seeking retribution. West Virginia Governor Cornwell barely avoided bloodshed by personally appealing to the miners.[19] Tensions were high.

The Spring of 1920 saw operators and miners clashing once again. Keeney and Mooney believed they had enough support in Logan County to petition for formal recognition of the mining union. However, it soon became apparent that the mine operators were unwilling to play ball. They fired and evicted any miner who signed a union contract. They also requested workers sign anti-union contracts. Soon enough, thousands of fired miners were seeking union relief.[20]

Mine operators turned to their old go-to for fighting strikes, Baldwin-Felts agents. Included with these detectives were the brothers of the head of the company, Albert and Lee Felts. Things begin to get interesting at this point because while in Mingo County, Albert Felts declared he was there to evict miners. Something the local mayor and sheriff declared he had no legal authority to do. Furthermore, he was acting without a warrant.[21]

Before going further, I just want to say that history is weird. You can be plugging along, expecting the story to continue as planned, when something out of nowhere can stop you dead. That happened to me when I read that the police chief of Matawan, the town that was the destination of the Felts brothers, was a man named Sid Hatfield. Yes, Hatfield, as in the Hatfields. Sid shared the same great-grandparents as the legendary William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield.

Sid liked shooting pool, playing cards, and enjoying a nice drink. He also enjoyed wearing two pistols, which he could draw quickly with each hand. Sid was dangerous.[22] It is also essential to note that Sid had worked the mines and found himself decidedly on the side of the miners.

Okay, back to the scene I started describing above, which historian Lon Savage excellently explains in his book Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920-21.

On Wednesday, May 19, 1920, the Felts brothers and their agents again entered Matawan, looking to evict miners from their homes. Sid confronted Al Felts when the agents entered a miner’s camp to enforce their evictions. The agents claimed they had the right to evict the miners, so Sid returned to town to confirm. Sid called the county sheriff, who told Sid that the agents had no right to evict miners and that Sid should arrest the agents.

A delighted Sid approached Al Felts upon Felts’s return to Matewan. Sid went for an arrest when Felts countered that he had a warrant for Sid’s arrest. The town mayor, Cabell Testerman, raced to Sid’s rescue and declared that the warrant for Sid’s arrest was bogus. Tensions were high as armed miners and agents watched the men. Here is where things get hazy, and the story enters into West Virginia lore.

Someone shot first. Sid claims Al Felts fired, while the Felts family claims Sid fired. In the end, no matter who fired first, the mayor was fatally shot in the stomach. The reason the Felts family had to claim Sid fired first was because Al was shot through the head and died. The armed miners and agents who had been watching opened up, firing upon each other. The battle claimed the lives of the mayor, the two Felts brothers, five agents, and two miners.[23] It would become known as the Matewan Battle.

It is hard to say who actually opened fire first. It appears well within the capability of both parties. However, one fascinating piece of the story is that the Felts family claimed that Sid shot first and killed the mayor because he was in love with the mayor’s wife, Jessie. I know this sounds like just a good story that the Felts used to make Sid look bad, but Sid married Jessie not long after the shooting.[24] Make that of it what you will.

Violence continued to escalate in Mingo County, with shootings occurring regularly. Making matters worse, someone shot and killed a grand jury witness who had recently testified against Sid and other miners in the Mantewan Battle.[25] The man arrested for the crime was a defendant in the Matewan Battle case. Regular shootings and a witness being killed led Governor Cornwell to make a hard decision to bring in federal troops.

Federal troops brought control to Mingo County in the following months, and by the fall of 1920, things were so good that they were recalled. However, multiple dynamite explosions, shootings, and the killing of a state trooper changed the minds of West Virginia officials. They asked for the federal troops to return. By the end of November, the troops returned to Mingo County, having only been gone for twenty-four days.[26]

The story of Sid Hatfield has a tragic end. While Sid had been acquitted of the murder of the Felts brothers and agents, he was still charged with conspiracy related to other miner violence in the state. On the morning of August 1, 1921, Sid, his wife, his co-defendant Ed Chambers, and Chambers’ wife all made their way to the courthouse steps for the trial. Baldwin-Felts agents opened fire on the two men as they stood on the steps. Both were killed.[27]

Violence was escalating in West Virginia. In August 1921, nine thousand armed miners prepared to march into Logan County to fight for their demands. However, there would be nearly three thousand armed guards waiting for them. It was looking like there would be violence of epic proportions. Enter Mother Jones in an attempt to calm tensions.[28]

Mother Jones was always successful in raising miners’ energy and pushing the workers’ agenda. However, it turns out she wasn’t so great at calming things down. Jones produced a fake letter from President Harding saying he would help the miners if they returned home. Mining leader Frank Keeney called her bluff and asked for the letter. He then let the miners know it was a fake. Jones’s time with the miners of West Virginia was over, and violence appeared imminent.[29]

The only thing that prevented a mass battle was the meeting between Keeny, Mooney, and Brigadier General Harry H. Bandholtz. Bandholtz did not hold back when he told the two leaders that if they didn’t turn back the miners, then Bandholtz would have the military forces take care of things.[30] I don’t think we have to guess why this conversation convinced Keeney and Mooney to turn back the miners. It is one thing to face heavily armed guards, but an entirely different thing to face the United States military.

It would have been nice if things had calmed down after this incident, but Sheriff Don Chafin of Logan decided not to let things settle. On the afternoon of August 27, Chafin chose to arrest a group of miners for a previous transgression. While marching their prisoners through the town of Sharples, Chafin’s deputies ran into a group of armed miners. Naturally, a shootout occurred, and two miners were fatally wounded.[31] Great job, Chafin.

I will give you three guesses on what happens next. If you need more than one, I will be confused if you read the article. That’s right, miners marched on Logan County again. The following weeks would be filled with constant violence as the Battle of Blair Mountain raged.

The Battle of Blair Mountain is wild to read about because it happened in the United States during peacetime and against its own citizens. Starting on August 31, armed miners began assaulting Blair Mountain and its defenders, led by Sheriff Chafin. Chafin’s men may have been outnumbered, but they had the high ground. They also had machine guns and planes. Yes, planes. Chafin hired private planes to drop homemade bombs on the attacking miners.[32] I couldn’t find exact casualty numbers since they range from 16 to 100. The fact that they are relatively low is a miracle, all things considered.

The battle stopped when federal troops arrived on the scene on September 2. Far from being frightened by the arriving army, the miners appeared happy.[33] They surrendered en masse. By all appearances, the miners never intended to fight the United States military. Their objective was the miner operators and their guards.

The Battle of Blair Mountain ended the West Virginia Mine Wars. The following years would be a mixed bag for miners. Many would see themselves accused of treason, only to be acquitted, but some did have to serve time. The mine guards were not subject to the same level of scrutiny as Sheriff Chafin, considering he was allowed to keep his job. However, several years later, Chafin was arrested for operating a speakeasy.[34] A real law-abiding citizen, that Chafin.

Miners eventually achieved their goals, but not until the 1930s. They also would not achieve anything through violence. Miners won their victories through legal battles and leveraging their combined voting power. The Mining Wars live in West Virginia’s history and legend.

[1] David Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 2nd ed. (Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press, 2015), 10. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/20/monograph/book/42339.

[2] James Green, The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom (New York, NY: Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated, 2015), 30.

[3] Corbin, 10.

[4] Green, 34-35.

[5] Green, 35.

[6] Green, 111.

[7] Corbin, 10.

[8] Green, 114.

[9] Green, 116.

[10] Corbin, 117.

[11] Corbin, 90-91.

[12] Green, 185.

[13] Green, 143.

[14] Corbin, 95.

[15] Green, 180.

[16] Green, 185.

[17] Corbin, 99.

[18] Green, 222.

[19] Corbin, 200.

[20] Hoyt N. Wheeler, “Mountaineer Mine Wars: An Analysis of the West Virginia Mine Wars of 1912-1913 and 1920-1921,” Business History Review (pre-1986) 50, no. 1 (

[21] Green, 265-66.

[22] Green, 254.

[23] Lon Savage, Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920-21 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990), 42-47.

[24] Savage, 50-51.

[25] Savage, 55.

[26] Savage, 64.

[27] Green, 313.

[28] Green, 325-27.

[29] Green, 326-27.

[30] Green, 337.

[31] Green, 340-41.

[32] Savage, 184-215.

[33] Green, 357.

[34] Green, 360.

Leave a comment