Passing Smoot-Hawley

Picture this: You’re a Republican in Congress in 1928. You’ve controlled the government for the last eight years, and the economy is booming. So, what do you want to do next? Is it introducing painful tariffs that mess with international trade? If not, you’re not a Republican Congressman in 1928.

The situation I presented may be hypothetical to you, but it wasn’t for Republicans in 1928. They were largely in control of the federal government throughout the 1920s. The decade had been one of growth and prosperity for the United States. It would seem like a time when Republicans would not advocate for significant policy changes. However, that wasn’t what some Republicans were thinking in 1928. No, they were thinking they needed to increase tariffs.

The result of the Republicans’ desire would be known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (SHTA). The SHTA is probably the most infamous tariff act passed in the history of the United States. Countless economists and historians have criticized it. It has even been blamed for causing the Great Depression. To be fair, it did not cause the Great Depression. However, it was not a good act. So, what was it? Why was it passed? Why do people think it caused the depression? And what was its actual impact? I will answer these questions for you, dear reader.

For those who don’t know, tariffs are government taxes on imported goods. There are ad valorem tariffs, which are a percentage of the good’s value, or specific tariffs, which are a set amount regardless of value. For ad valorem, it’s simple if you charge 5% on an item, you will just charge 5% on its current market value. Specific tariffs seem like they’d favor the imports because the tax remains the same no matter how high the value goes up. However, if the value of an item goes down, the relative cost of the tariff increases. A $100 tariff hurts much less on a $500 item than on a $250 item. Quick note: Two-thirds of US imports used specific tariffs when Congress enacted the SHTA.[1] Things could not have been fun when pricing started dropping. Now, back to the story.

On the surface, the reason Republicans liked tariffs makes sense. They tended to come from the manufacturing-heavy northern states. Of course, they want to protect their industry from overseas competition. But in 1928, it wasn’t industry Republicans were looking to protect. No, they wanted to save the struggling agricultural market.[2]

US agriculture found itself in an odd position in the 1920s. It had experienced a significant boon from WWI, which in turn led to large capital investment. However, after the war ended and the increased need for US agriculture decreased, many farmers struggled to pay for the investments they had made during the war.[3] It is perfectly reasonable for Congress to want to help the agricultural section of the economy.

Recognizing that the US exported far more agricultural products than it imported, the first attempt to help farmers was to subsidize exports. This plan fell apart when President Coolidge vetoed the bill. The veto led the farming supporters to tariffs.[4] I’m not sure how it makes sense for tariffs to help when the US exports more than it imports, but Congress thought it could.

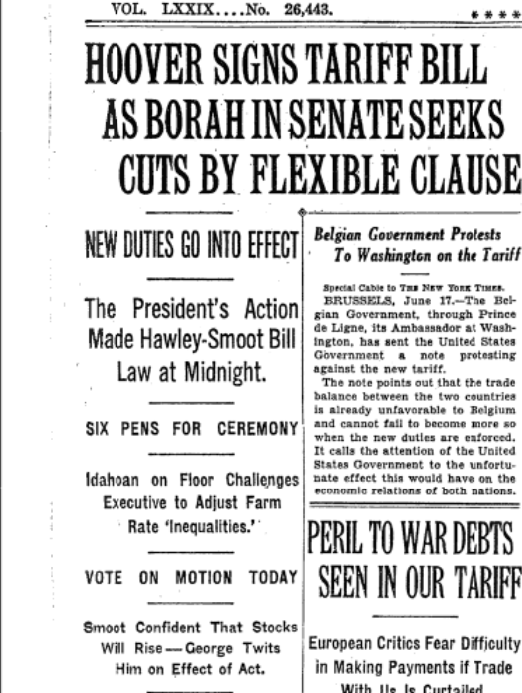

The tariff process was long and arduous, with numerous revisions. The SHTA bill took 1.5 years from inception to passing. After the bill left the House and went to the Senate, it had to go back to the House because of all the changes made in the Senate. It was first proposed in January 1929, before the start of the Great Depression, and was passed in June 1930 when the economy had already begun to collapse.[5]

Why did it take so long? Well, it may shock you, but politicians wouldn’t let this act pass without getting their hands on it. Instead of focusing solely on agriculture, Congress looked at the entire tariff schedule (yes, the US had existing tariffs already). After all the revisions, the final bill led to 890 increases, 235 decreases, and 2,170 duties unchanged.[6] Suddenly, this goal of helping farmers has majorly changed international trade relations for the US.

I’ve bypassed a lot of political back-and-forth during the year and a half that Congress took to pass the SHTA. It is fascinating, but it would stretch this article beyond its intended purpose. However, I want to make the point that politicians spent a lot of time negotiating and using political capital to pass an act that would become infamous. They probably felt like real dummies.

Now that I’ve provided a quick history of why Congress looked into the SHTA and how it transformed into a far more overreaching bill than anticipated, I want to cover the repercussions. I will go down the list of things people blamed on the SHTA.

Caused the Stock Market Crash and the Start of the Great Depression

The SHTA’s reputation as a disaster likely started when a thousand economists signed a letter speaking out against the act. Then in 1976, economist Allen Meltzer placed a large amount of blame on the SHTA for worsening the recession into a depression. Meltzer argues that the tariffs led to an influx of US gold, with initial exports declining very little. This shocked the global system, leading other countries toward deflation. Obviously, this would be a negative once US exports decrease in the coming year. Furthermore, the eventual decrease in agricultural exports led to agricultural bank failures.[7] Everything I read referencing Meltzer disagreed with most of his assessments. There was no large influx of gold after the SHTA was passed. Furthermore, while his agricultural argument makes sense, it ignores the large drought that hit the major farming states.[8] The drought was likely the more significant contributor to the agricultural issues.

The bill itself could not cause the stock market crash in October 1929, mainly because Hoover would not sign it into law for another seven and a half months. However, reading about the SHTA, I noticed historians mentioned that some people believe the debates surrounding the bill and the uncertainty they created caused the crash in 1929. Historian Douglas Irwin disagrees with this assessment. He points out that the crash of 1929 was focused mainly on public utility companies, which would be the least impacted by tariffs.[9] I could not find a strong argument beyond uncertainty for blaming the crash on the bill. So, no, the SHTA did not crash the stock market.

Interestingly, one of the strongest arguments for the SHTA’s impact was the bill’s impact on the early recession. Historians Robert Archibald and David Feldman argue that the uncertainty surrounding the bill limited capital investment in US firms. They conclude that you can tie the debates surrounding the SHTA to the recession that began in 1929. They don’t say it’s the single cause, but one of them.[10] It is not a conclusion heavily debated by other historians.

Aside from Meltzer, who was subsequently argued against by everyone I read, I could not pinpoint a good argument for the SHTA causing the crash during the Great Depression. The best I saw was that it played a role in making things worse, but was not the most significant factor.

Hurt American Imports

The idea behind the SHTA hurting imports is simple: If it costs more for companies to import goods into the United States, they’ll charge more, providing favorable pricing for domestic goods. Therefore, overall demand for foreign goods will decrease. It is an easy concept to understand, but did it happen with the SHTA? Yes, it did. Moving on.

Okay, I think you probably want a bit more of a detailed answer than that.

Irwin calculated a 40% decrease in imports in the years following the SHTA. However, the SHTA is only responsible for one-third of that 40%.[11] It is still an impressive figure in a time when America could not afford further reduction of imports, but it was not the sole or even most significant driver. Irwin believes the decrease’s most significant driver is lessening demand due to falling income.[12]

So, while my answer of ‘Yes’ above is still accurate, you can see there is a bit more nuance to the situation.

Significantly Hurt International Trade and American Exports

To answer this question, you must know the response to the SHTA internationally. Other countries were not happy. Europe thought it was poor timing when their countries were falling into a depression.[13] The international community responded in a way everyone should have anticipated. They retaliated.

Canada and the United States had a friendly, interconnected relationship. It must have felt like a betrayal to have your closest neighbor and ally suddenly put economic pressure on you. Canada responded to the tariffs by instituting their own. Canada’s response was devastating for US exports. US exports to Canada dropped by nearly 21%, which equated to an almost 4% drop in total US exports. This drop would remove any benefit to new import tariffs.[14]

Western Europe did not respond like Canada by issuing retaliatory tariffs. Instead, it decided to shift trade away from the United States. Historians attribute some of this to the natural shift toward protectionism due to the growing depression. However, as in the case of Britain, some of it was in direct response to the SHTA. Britain shifted its trade toward imperial preferences in response to Canada’s request.[15] Other countries would follow Britain’s lead and begin trading away from the United States.

The most significant consequence of the SHTA is its impact on Cuba. Cuba’s main export was sugar, and its biggest trading partner was the United States. This relationship meant that when the US put hefty tariffs on sugar imports, it crippled the Cuban economy. This downturn led to a revolution in 1933. Irwin points out that the revolution began distancing Cuba from the US.[16] Truthfully, I’m not sure if you can claim all subsequent governments as distancing from the US, but this revolution began the march toward Castro.

It is hard to say that the SHTA did not impact US exports and international trade. It forced retaliatory tariffs from some countries and discriminatory trading from others. Historians Kris James Mitchener, Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke, and Kirsten Wandschneider analyzed trade data. They concluded that even taking all other factors into account, US exports dropped at a disproportionate rate. Furthermore, they dropped even with countries not typically considered to have retaliated.[17] It becomes clear that the SHTA hurt America.

End of Smoot-Hawley

President Herbert Hoover was voted out of office in favor of Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in 1932. FDR knew a change was needed regarding the tariff policy. FDR pushed Congress to pass the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA). The RTAA granted the president the power to adjust tariffs as negotiated in trade agreements. RTAA represented a shift in US policy as trade agreements would define US trade policy from then on out.

So that was Smoot-Hawley, a bill designed originally to help farmers in a way that made little sense. However, due to special interest groups and politics, it became a bill that upended US international trade. Even though it didn’t cause the Great Depression, it hurt the economy at a time when the US and the world could not afford more damage.

[1] Douglas A. Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 107.

[2] Irwin, 17.

[3] Irwin, 18.

[4] Irwin, 20-25.

[5] Robert B. Archibald, and David H. Feldman, “Investment During the Great Depression: Uncertainty and the Role of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff,” Southern Economic Journal 64, no. 4 (1998): 860, https://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1061208.

[6] Douglas A. Irwin, Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 383-84.

[7] Allan H. Meltzer, “Monetary and Other Explanations of the Start of the Great Depression,” Journal of Monetary Economics 2, no. 4 (1976): 460-61, https://kilthub.cmu.edu/articles/journal_contribution/Monetary_and_Other_Explanations_of_the_Start_of_the_Great_Depression/6706907?file=12235931.

[8] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 132-34.

[9] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 79.

[10] Archibald, and Feldman 872-73.

[11] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 163.

[12] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 135.

[13] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 172.

[14] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 179-80.

[15] Irwin, Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression, 199.

[16] Irwin, Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, 397.

[17] Kris James Mitchener, Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke, and Kirsten Wandschneider, “Smoot-Hawley Trade War,” Article, Economic Journal 132, no. 647 (2022): 2521, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac006.

Leave a comment