Studying financial crises throughout history is a lot like studying wars. There are far too many of them, and each feels unique. If I were to continue to use my war metaphor (mainly because it is all I have), I would say the global depression that rocked the world in the 1870s is akin to World War I. Each is overshadowed by a greater follow-up. For WWI, it was WWII, and for the depression of the 1870s, it was the Great Depression. Furthermore, while a multitude of reasons caused each event, people credit one thing as the start. You can look at the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand for WWI. For the global depression of the 1870s, you have Jay Cooke’s financial failures and the resulting Panic of 1873.

This article is not about the global depression of the 1870s. It is not even really about the Panic of 1873. This article explores Cooke’s biggest failure and why he gets blamed for the Panic.

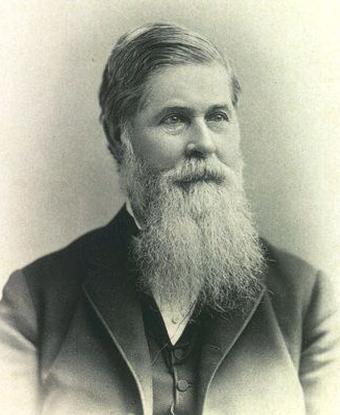

Cooke was not just an investor looking to expand his wealth by speculating on the railroad industry in the 1870s. He was the man in charge of one of the most powerful banking houses in the United States. Furthermore, people considered him the “financier of the Civil War.”[1] When the Union desperately needed funds during the Civil War, he helped raise nearly $1.5 billion in bonds for the Union, which was almost a quarter of all funds raised for the Union.[2] The Union would have been in trouble without Jay Cooke.

It is hard to give a modern comparison to Jay Cooke. There are people of equivalent financial strength and influence, such as Warren Buffet, but no one in recent memory is so closely tied to helping save the country. So, for the sake of this article, I’m going to need you to picture someone like Warren Buffet but make him an American hero. That is who Jay Cooke was in the 1870s, which makes his failure more shocking.

If you’re asking yourself, “Why should I care about this guy and his second-place financial crisis?” First, I hope you are here because you either like history or think I’m the best. Second, historians like Eric Foner credit the 1870s depression with leading to significant political overhauls.[3] If you read my Reconstruction article, that’s a big deal.

Cooke was hesitant to get involved with the Northern Pacific Railroad at first. He turned down the idea when officials first approached him in 1866.[4] However, in 1870, Cooke viewed things differently. It is hard to say what led to his change in mindset. However, the Transcontinental Railroad had just been built, and people viewed it as an outstanding achievement. Maybe he was influenced by the idea of cementing his legacy and creating something great. Or perhaps he just wanted to make a lot more money. Either way, by 1870, Cooke was in the Railroad business.

I’m going to spoil my article by saying that the simple reason the Northern Pacific bankrupted Jay Cooke was that he kept having to pour his own money into the venture. It ran into many issues, and bond sales were low. Cooke kept putting good money in after bad. What were the problems that kept bond sales low and forced Cooke to spend his own money?

Well, the issues involve two areas: land and people. When building a railroad, you rely on suitable land for smooth construction and competent leadership to help overcome any obstacle. It would be a struggle to make a railroad with one of these things working against you, but if both are subpar, you will find yourself in trouble. Cooke had both against him. I will focus on each part separately.

Land

Minnesota should have been an easy route for a train based on the idea that most of its land was relatively level. However, as historian M. John Lubetkin points out, no other area was more riddled with issues.

“For over a hundred miles, the area consisted of porous glacial moraine with lakes, swamps, peat bogs, sloughs, pine barrens, sinkholes, quicksand, and sometimes floating “islands” of solid ground. Beside visible creeks and rivers, underground streams flowed just below what appeared to be firm land.”[5]

Making matters worse is that standing water is notorious for producing mosquitos. Things would get so bad that mosquito clouds would form, resulting in dead animals and suffering workers. I can’t stand one mosquito bite, so I can’t possibly imagine being covered in them. I know if I am I’m not focusing on my work. Parts of the track that should have been easy to build suddenly took time and cost precious dollars.

A large part of railway construction is surveying land for track. In the 1870s, the land may not have been unexplored, but it wasn’t mapped. Surveyors were required to map out the land for construction. It sounds like an easy enough job, but tensions between the expanding United States and the Native Americans made surveying a problematic task.

Native Americans were rightfully concerned that as the United States moved west, they would slowly lose their land. So, the Native Americans fought back, which impacted the surveyor’s ability to map the land. Making matters worse for Cooke was that not all stories about the Native Americans were true. Many exaggerated tales turned away investors from the prospect of investing in westward expansion.[6]

Just because the press would exaggerate some of the stories does not mean there weren’t real issues. The surveyors and the army units sent to protect them clashed with both the Lakota Sioux. It is here where Cooke’s dream intersects with history once again. One of the men sent to protect Cooke’s surveyors was Major General George Custer. While protecting surveyors in the Dakota Territory, Custer and his men met their tragic end. If the Northern Pacific Railroad did not try to go through the Dakota Territory, Custer might not have become famous for his defeat. So not only does Cooke shoulder the blame for a financial crisis, his name is attached to one of the United States biggest military defeats. Good job, Jay.

So, let’s review. Construction took longer and cost more because the land chosen had more obstacles than initially planned. Surveying delayed expansion because they could only move at a slow pace due to the battles with the Native Americans. Compounding matters, Cooke struggled to get new investors because the stories of the fight with the Native Americans scared away potential investors.

People

The Northern Pacific might have succeeded under Cooke’s watch had the men he put in charge properly operated the company. Cooke placed J. Gregory Smith at the head of the Northern Pacific. Smith was a businessman and former governor of Vermont. Smith was not the right man for the job.

Smith had recently run his company, Vermont Central, into the ground, and there were some thoughts he may have been misusing the company’s resources.[7] I’m unsure if Cooke was aware of Smith’s misuse of company funds, but he should have been aware of Smith’s skillset. Lubetkin states that Smith had no experience in large-scale construction. His history with the Vermont Central Railroad saw slow growth, but the Northern Pacific required rapid growth. Smith didn’t have the experience needed. Did I mention Smith was not the right man for the job?

One of the means of income for the Northern Pacific and its investors was selling land around the railroad to settlers; however, Smith first needed to certify the land to sell it. Northern Pacific did not certify a single acre of land in 1871 or 1872.[8] This was due to Smith and his management. He kept delaying the certification process, costing the railroad and, in turn, Cooke millions. Worse, Smith was incompetent in a lot of ways. On top of not certifying the track, he also decided that the Northern Pacific needed 50 “first class” Baldwin locomotives when they had already purchased 48 locomotives.[9] That’s just what your railroad needs when it’s hemorrhaging money and still under construction, first-class locomotives. One last time, Smith was not the right man for the job.

The board’s decision to agree with all of Smith’s requests was amplifying matters. They basically did whatever Smith wanted and made no effort to correct his terrible stewardship. Cooke finally managed to remove Smith in late 1872. However, the board still made matters worse. The board was split on a replacement, so the Northern Pacific went 4 months without someone in charge.[10] It was not the right board for the job.

The last person to mention is someone not involved in the Northern Pacific Railroad but an employee at Jay Cooke & Co. Harris C. Fahnestock ran the New York office of Jay Cooke & Co. and was 14% owner of the bank.[11] He was against Cooke investing so much of his money into the venture. A generous reason for Fahnestock’s feelings is that he thought Cooke would likely bring down the bank through his railroad business. Another reading would show that Fahnestock had fallen into JP Morgan’s orbit.[12] Morgan and Cooke were rivals, and Morgan’s influence on Fahenstock could only negatively impact the latter’s opinion of Cooke. This new relationship, plus Fahnestock’s desire to maintain his personal fortune, led him to close the New York branch of Jay Cooke & Co. on September 18, 1873.[13] Things were bad in general for Jay Cooke & Co., but Cooke’s use of funds to help his railroad amplified things greatly. Cooke may have been able to salvage the New York office’s struggles given time, but Fahnestock gave Cooke no chance to save the situation.

The closing of the New York office doomed the bank. It would also send shockwaves throughout Wall Street and the world. The bank’s closure and global issues led to a worldwide panic. There were bank runs and layoffs, and suddenly, the world collapsed. Ironically, Fahenstock hurt himself with this forced closure. JP Morgan stepped up to fill the newly created banking void, and Fahenstock was left outside looking in.[14] Fahenstock’s friendship with Morgan amounted to nothing once money was involved.

If you’re wondering how Jay Cooke & Co.’s closing could lead to such a panic, the events of the 2008 financial crisis might prove to be a good comparison. Global economies were already showing signs of distress, but Bear Stearns was looking at bankruptcy, and the world panicked. Jay Cooke and Co. is Bear Stearns in this situation. Plenty of global issues in 1873 showed the global economy was in distress, but people only panicked when one of the largest banks went down.

Along with the bank, Cooke also declared personal bankruptcy. The notice to creditors shows Jay Cooke only owing about $81,000 between two mortgages.[15] However, this is in the 1870s, so the value would be slightly over $2 million. Cooke moved in with his daughter after declaring bankruptcy.

There is a bit of a happy ending to this story. Jay Cooke eventually regained some form of a fortune, but never to his previous levels. More importantly, the Northern Pacific Railroad was ultimately completed in 1883. It was too late to do Jay Cooke any good, but at least the workers’ effort was not wasted.

So there you have it: Cooke’s big failure. I think it is unlikely that had the Northern Pacific been more successful initially, that much would have changed globally. The world was trending toward a global depression no matter what. All Cooke did was blow the whistle to start the game.

[1] M. John Lubetkin, Jay Cooke’s Gamble: The Northern Pacific Railroad, the Sioux, and the Panic of 1873 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press 2014), 3.

[2] Lubetkin, 11.

[3] Eric Foner, Reconstruction Updated Edition: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-18 (HarperPerennial Publishers, 2014), 718.

[4] Christopher P Munden, “Jay Cooke: Banks, Railroads, and the Panic of 1873,” Pennsylvania Legacies 11, no. 1 (2011): 5, https://dx.doi.org/10.5215/pennlega.11.1.0003.

[5] Lubetkin, 5.

[6] Lubetkin, 171.

[7] Lubetkin, 35.

[8] Lubetkin, 166.

[9] Lubetkin, 162.

[10] Lubetkin, 164.

[11] Munden 5.

[12] Lubetkin, 172.

[13] Munden 5.

[14] Lubetkin, 285.

[15] Jay Cooke et al., In the Matter of Jay Cooke, William G. Moorhead, Harris C. Fahnestock, Henry D. Cooke, Pitt Cooke, George C. Thomas, James A. Garland, and Jay Cooke, Jr., Copartners, & Co., in Bankruptcy (Philadelphia: Allen Lane & Scott’s Printing House, 1873), 79.

Leave a comment