Writing a short-form article about Reconstruction is not an easy proposition. It is a dense topic that easily has filled thousands of pages. Historians have written books focusing on singular aspects of Reconstruction just so they could do them justice. I’m not going to pretend that I will be able to fully convey the history of Reconstruction. That is not even my goal. This article is designed to give a quick overview of what it was, why it happened, and, ultimately, why it failed.

With that in mind, it is time to provide a few caveats for the article. These are designed to help keep the article short and consumable. First, this will focus primarily on the South. The North and West underwent their own transformations during this time, but covering them would go above and beyond the intended purpose of this article. Second, I’m going by the period as defined by historian Eric Foner. He defined Reconstruction as occurring between 1863 and 1877. I know some historians have argued that Reconstruction lasted beyond 1877, but that would again go beyond my intended scope. Third, I’m going to avoid discussing the historiography of Reconstruction. That is a book on its own. Finally, I will avoid getting into the historical “what ifs?” surrounding Reconstruction. Many historians debate how things would have played out had Lincoln lived. While this may be a fun exercise, I think it would likely drag this article down considerably.

Now that everything is out of the way, we can get on to the article. Thanks for reading!

While the Civil War raged and emancipation was becoming a reality, the Union leaders realized they needed to understand how to piece the country back together. If they won the war, they would suddenly find themselves reunited with the very people who seceded from the Union and turned traitors. Furthermore, they would suddenly have millions of formerly enslaved people (commonly referred to as freedmen) for whom they had no plans. Union leaders needed to set a course, but unfortunately, division among Republicans would set the tone for Reconstruction.

The first battle of Reconstruction would be between President Lincoln and the radical members of his own party. Lincoln proposed a plan that would see the pardon of most people should they take an “ironclad” oath of future loyalty and pledge to accept emancipation. His plan would exclude high-ranking civil and military officers in the Confederacy. Once 10% of a state’s voters said the oath, the state could establish a new government.[1]

The Radicals offered a different plan, the Wade-Davis bill. The Wade-Davis plan demanded that a majority of the state’s white males pledge to support the federal Constitution. Furthermore, under the plan, only those who had taken the oath could vote in the state’s constitutional convention. The plan would also offer equal standing under the law for freedmen but not the right to vote.[2]

The Radicals may have been the strongest voice, but the Wade-Davis bill was popular even among more moderate Republicans. Congress managed to pass the bill, but Lincoln pocket-vetoed it. While this may look poorly on how Lincoln would handle Reconstruction, Eric Foner, one of the premier Reconstruction historians, advises against viewing Lincoln’s proposal as a hard and fast policy. Instead, he states it was “a device to shorten the war and a plan to help solidify white support for emancipation.”[3] We can never know what Lincoln would have done during Reconstruction. However, it is pretty easy to say that it is likely different from his successor, Andrew Johnson.

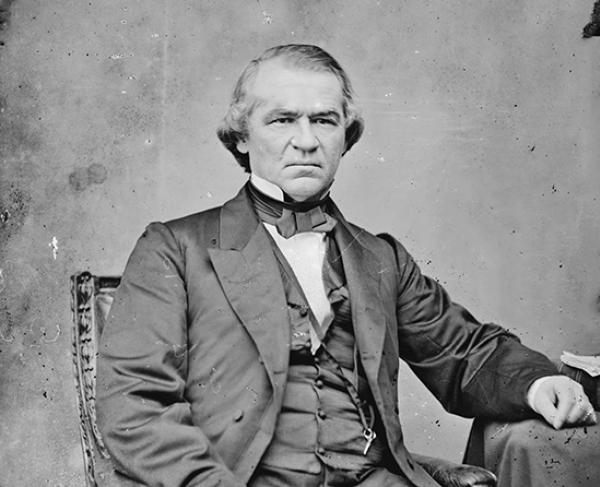

Andrew Johnson’s road to the White House would have been unique even without the assassination of President Lincoln. He was a Democratic senator from Tennessee who stayed loyal to the Union when Tennessee seceded. He was then placed as a military governor of the state once the Union recovered large swaths of the territory. Finally, Lincoln thought it wise to nominate Johnson as his Vice President. Also, he looks a lot like Tommy Lee Jones. Check out his picture below. You’ll see I’m right.

I’m not sure if there could have been a worse replacement for Lincoln. Johnson fancied himself a Jacksonian Democrat who adamantly believed in state’s rights. He could be considered rigid to a fault. Historian Michael Fitzgerald considers him “the least flexible leader possible at the most sensitive moment in the nation’s peacetime history.”[4] Finally, Johnson would be considered racist by any definition. Johnson fit in with his fellow Republicans with his stance against slavery. However, historian Allen Guelzo believes his real animosity was not toward slavery but was related to his hatred of the aristocracy and planter class.[5] He was not the man you wanted leading Reconstruction.

The crazy thing is that Republicans had high hopes for Johnson at first. They thought he would lead to massive changes in the South.[6] His initial policy would see the amnesty and pardon of any Southerner willing to swear an oath of loyalty. They would also see a return of their property. The sole exclusion was anyone with property valued at more than $20,000. Those Southerners had to apply individually for amnesty. It appeared on the service that Johnson was keen on keeping the pre-war elite out of politics. However, in practice, this idea fell apart quickly, and by 1866, Johnson had granted amnesty to 7,000 Southerners excluded in the $20,000 rule. This number is out of 15,000 people who met the exclusion criteria.[7] Johnson was putting the government back in the hands of those who had led the fight against the Union.

Abandoning his own plan was only one part of Johnson’s fight against radical Reconstruction. He vetoed almost every bill presented by the Republicans, and he was at war with his party. The battle would continue to get uglier and uglier. You may be asking why Johnson changed from his original plan. Why was he at war with his party? Guelzo suspects it’s because he wasn’t looking to keep the Southern aristocracy away; instead, he wanted them to approach him on bended knee to experience humiliation.[8]

Another explanation is that Johnson simply was racist and wanted a solid white government. Foner covers the experience of a New York Evening Post editor who witnessed Johnson railing against the treatment of Southern whites in defense of Blacks.[9] It’s hard to doubt Johnson’s racism based on these experiences and his opposition to Black suffrage. He was one of the biggest opponents of giving Black people the right to vote.

The Republican-led Congress was not about to take Johnson’s tactics lying down. In February 1867, they passed four Reconstruction bills that removed Johnson from the equation. The first eliminated the Reconstruction state governments and placed the military in control. The second bill created a registry of eligible voters that excluded all ex-Confederate leaders. The third and fourth helped determine how military leaders could remove uncooperative leaders and created residency requirements. Johnson tried to veto these bills, but Congress overrode him.[10]

Johnson’s political prospects were essentially over as the 1868 election loomed. Congress had just shown further disdain for Johnson by passing the 14th Amendment in July 1868. The amendment guaranteed equal protection under the law for Black Americans. Johnson had become a pariah within his party, and the Democrats were not likely to accept him.

However, Johnson would have the final laugh when he granted a general pardon to all ex-Confederates before he left office. He had ensured that the old elite could control the South once again. Johnson started the process of the demise of Reconstruction. Oh, and he really looked like Tommy Lee Jones.

Ulysses S. Grant would be the next up to try his hand at Reconstruction. However, before delving into his term as President, it is essential to explain what happened in the South during Johnson’s term. The freedmen and the former masters were not sitting idly by as politicians played games. Southerners were determined to control their destiny.

It should be of no surprise that formerly enslaved Black people wasted no time in embracing their new freedoms. They walked the streets more freely, talked back to their former masters, and traveled where they liked. Traveling freely seemed to be an especially prevalent choice.[11] It flew in the very face of the restrictions for which they had lived for so long.

Furthermore, Black people were driven to obtain land. Even if it were just a tiny piece, this land would provide a measure of wealth and security. Black people would also farm this land, but more for subsistence than economic gain. For those who could not gain land, they wanted better working conditions away from the old ways of slavery. They especially sought to rid themselves of the overseers.[12]

Black people also sought to reshape their home lives. Women who often worked the fields beside men began staying home like their white counterparts. They would be responsible for the housework while their husbands worked the fields. Furthermore, schooling became vitally crucial for the Black community. Black people went to work constructing schools, and black children were now spending their days being educated instead of working alongside their parents.[13]

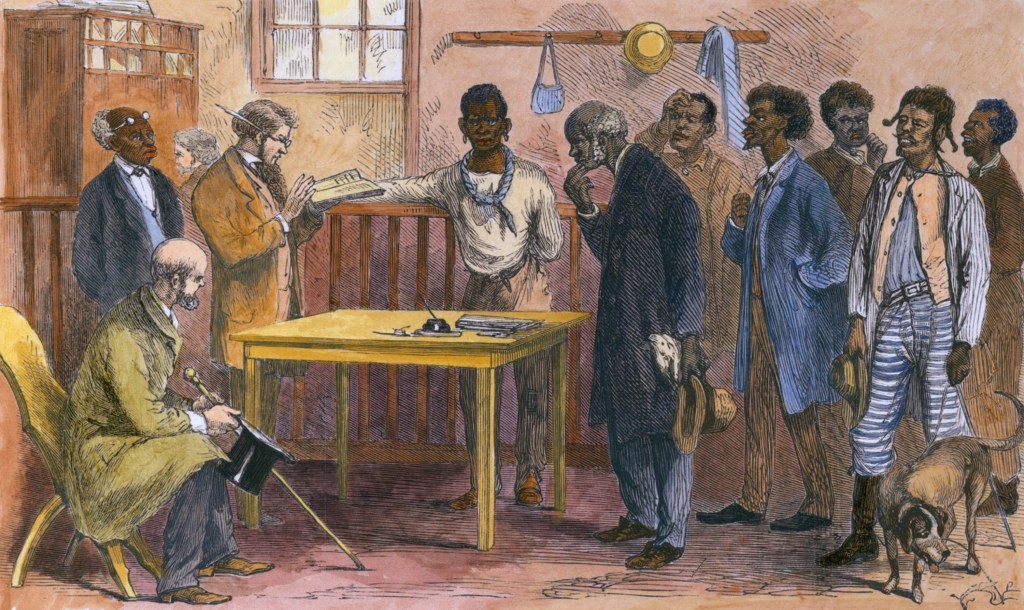

It may shock you, but the former slave masters were unhappy with the situation in which they found themselves. They did everything they could to change things back in their favor. States like Mississippi and South Carolina began enacting Black Codes. These codes forced Black workers into year-long contracts. Whites would enforce these contracts with harsh discipline reminiscent of plantation life.[14] Congress repealed these acts with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, but their legacy lived on in the Jim Crow laws.

When the law failed to keep Black people subservient, violence took its place. Terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) began attacking Black people both in public and in their homes. Things would worsen as Blacks received the right to vote. The KKK would do what they could to prevent them from exercising this right.[15] Terrorism would be a defining characteristic of Reconstruction and the South.

Separate from these groups was a collection of people looking to make money on the changing Southern landscape. This collection consisted of two groups with great nicknames. In group one, you had people from the North coming down to the South to try to make money. Southerners who favored the old ways called these newcomers carpetbaggers based on their luggage. The second group were born and bred Southerners who worked with Republicans called scalawags. These scalawags had differing motivations for working with Republicans, but economic self-interest certainly played a role for some.[16]

The big economic movement was railroads. As movies and TV have told us all, railroads were a big deal following the Civil War. The South was not exempt, as investors with dollar signs in their eyes looked at the changing Southern landscape and moved to put down tracks. Railroads undoubtedly provided jobs through construction. In states like Georgia, railroads also shifted trade away from river-based commerce to railroads connected directly to the Eastern markets.[17] Railroads were expensive and often required bonds or government aid. When the economy entered a depression, the railroads went bankrupt, and suddenly, their revolutionary image lost its shine.

Grant took his spot in the White House in 1869, and luckily for Republicans, he was not another Johnson. Grant may have been more moderate than some of his Republican counterparts, but he had no intention of fighting them to complete the Reconstruction of the South. An excellent example of their differences is that Grant, unlike Johnson, was not against Black suffrage. He supported the Fifteenth Amendment, which made it illegal to prevent someone from voting based on race. Johnson would have likely fought it tooth and nail.

Grant’s first two years saw him taking a more hands-off approach to Southern policy. He pushed very few initiatives.[18] However, the South would not let Grant stay quiet for long. The KKK only increased its terror activities, and violence was becoming part of everyday life for Southern Blacks and Republicans. Grant and Congress responded by passing the Ku Klux Klan Act in April 1871. This Act led to over 6,000 arrests of Klan members and helped suppress violence in the South.[19]

While the KKK Act was effective, it could not prevent all violence. In April 1873, one of the worst acts of Southern Violence took place. Local elections in 1872 created rival claims to power in Colfax County, Louisiana. Black residents feared that Democrats would seize power, so they cordoned off the town of Grant Parrish, which was the county seat. The Black residents managed to hold the town for three weeks, but on Easter Sunday, the white attackers overwhelmed them.[20] The exact number of casualties is unknown; a monument dedicated to the Massacre in April of 2023 lists the names of 57 dead. However, the number could be over 100.

Republicans were fighting hard for Reconstruction and seeing solid gains. However, as the years passed, the gains began to fade. Although they still held the White House and Congress, it looked like they were losing the South. So why did Reconstruction fail? It comes down to three things, in my opinion: economics, politics, and time.

Economics

A man named Jay Cooke, through his company Jay Cooke and Co., set the country on the course for a depression. How? They decided to raise millions of dollars in bonds to fund their railroad construction. When they couldn’t pay the bonds back, they created a cascading effect that brought the American economy to its knees. I know this is a simple explanation, but going into more detail would distract from the point.

The depression was felt all over the United States, including the South. Cotton prices fell nearly 50 percent between 1872 and 1877, driving farmers to poverty. Agriculture suffered across the board. Workers of all races felt the bind of the depression.[21]

It doesn’t take a student of history to realize two things happen when a depression hits. First, people stop worrying about things other than economics. Second, the party in power generally loses power. The depression helped open the door for Democrats to regain seats in all areas of the country.

Politics

It wasn’t just the depression costing the Republicans power. Southern Democrats started a new policy of “redeeming” the South. “Redeeming” meant putting whites back in power and taking away the hard-fought gains of Black people. These Democrats could do this because many former Confederates had re-entered the voting base. I’m sure in no small part to the pardons issued by Johnson. However, they didn’t just rely on sheer numbers to win. They would endorse dissident Republicans, focus on economics instead of race, and, when all else failed, gerrymander.[22] If those things failed, they could always fall back on violence.

Time

If everything had happened in a more condensed timeline, Reconstruction may have stood a chance against the economy and the political machinations of Democrats. However, the Northern public grew tired of focusing on the South as the years stretched. Northern citizens had their own concerns and wanted to move on from Reconstruction.[23] Republicans had lost momentum, and the South would pay the price.

If you’re wondering when Reconstruction officially died, it happened on March 2, 1877. That is the day Rutherford B. Hayes was elected President of the United States. Why was his election the end? The election of 1876 resulted in a disputed set of electors, and even after a commission came back granting Hayes the electoral votes, it looked as if the outcome could split the country again. Hayes, to prevent this split, compromised with the Democrats. He would essentially surrender the South to Democrat control and remove all federal troops, and they would stop fighting about the electors.[24] I need to point out that the actual terms of the agreement are unknown since there is no record of the agreement. What is known is that the Democrats got what they wanted in the South, and Hayes got to be President. How nice for him.

So ended Reconstruction. It looked like it could achieve something tangible for much of its time. It had the chance to provide equal rights to all people, not only in the South but throughout the country. Unfortunately, not everyone wanted that, and in the end, those against Reconstruction played the long game and won.

[1] Eric Foner, Reconstruction Updated Edition: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-18 (HarperPerennial Publishers, 2014), 87.

[2] Foner, 120.

[3] Foner, 87.

[4] Michael W. Fitzgerald, Splendid Failure: Postwar Reconstruction in the American South, American Ways (Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, 2008), Chapter 2, Kindle.

[5] Allen C. Guelzo, Reconstruction: A Concise History (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), 17-18.

[6] Foner, 272.

[7] Foner, 290.

[8] Guelzo, 21.

[9] Foner, 402.

[10] Guelzo, 40.

[11] Foner, 145.

[12] Foner, 176-81.

[13] Fitzgerald, Chapter 3, Kindle.

[14] Foner, 301-02.

[15] Foner, 487.

[16] Foner, 429.

[17] Fitzgerald, Chapter 5, Kindle.

[18] Foner, 634.

[19] Foner, 611.

[20] Foner, 607-08.

[21] Foner, 707.

[22] Foner, 577-87.

[23] Foner, 623.

[24] Guelzo, 113-14.

Leave a comment