Imagine for a second you’re a young man in your early twenties. You’re a revolutionary at heart and want nothing more than to take part in the war to free your country. Now imagine one of the rebels’ leaders asks you to join an elite squad that will be used for some of the most sensitive and essential missions. These missions would be dark and dangerous. You will be used to kill countless enemies up close and personal. Would you balk at the offer, or would you take the job? In revolutionary Ireland, a group of twelve men were given this offer, and they accepted it enthusiastically. They were Michael Collins’ Twelve Apostles, and their actions are as infamous as they are legendary. Here is their history.

To understand these men’s jobs, you must first know that the Irish War of Independence was a guerilla war by all definitions. It featured quick hit-and-run attacks by IRA units in the country and assassinations by IRA units in the cities. Michael Collins’ Apostles, also known as the Squad, were the urban fighters, the assassins. They walked the deadly streets of Dublin, removing high-value targets. When Collins, the de facto leader of all military and intelligence operations, wanted someone dead, all he needed to do was call on the Squad. They were the gun in his hand.

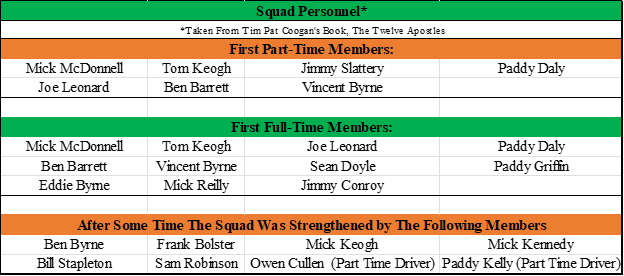

Before going further, it is essential to provide the membership of the Squad. Below is the roster as it developed and changed over the years per historian Tim Pat Coogan.[1] You will quickly note how there never seemed to be precisely twelve members at any time. Apparently, the IRA liked to be poetic when naming groups. It should also be noted that the group below and the focus of this article is the Squad out of Dublin that operated directly under Collins. Other squads would appear in different areas of Ireland (never let a franchise idea pass you by), but they are not the focus.

The formation date of the Squad is a matter of debate between the members and historians. Consensus founding leader Mick McDonnell put the formation as of May 1, 1919. However, Paddy Daly claims the formation date was September 19, 1919. Paddy also would claim that he was the group’s original leader, so make of that what you will. Finally, Vinny Byrne would argue that the group formed in March 1920.[2] To make matters more confusing, author and Sinn Féin party member Piaras Béaslaí wrote in 1926 that the group formed in July 1919.[3] The confusion does not result from malice but rather a simple human memory error. These were all men remembering the formation years after it occurred. Time has a way of blurring the truth.

What can be confirmed is that one of the first killings by members of the group happened on July 30, 1919, with the shooting of Detective Sergeant Patrick Smyth. Operations continued from that date. Historian T. Ryle Dwyer attempts to reconcile Byrne’s date with McDonnell’s by saying that two elements of the Squad were working at this time, and they did not unite until March 1920, which would officially mark the beginning of a unified unit.[4] Regardless of the exact circumstances, one fact remains. By July 1919, the Squad was hunting.

So, how did their job actually work? First, a member of the IRA would identify a potential target to Collins’ intelligence staff for various reasons. If Collins agreed with the assessment, then the Squad had their target. The Squad was given explicit instructions that killing based on their own determination or desires was banned. The assigned members would consult with the IRA member who initially selected the target. This non-Squad member would accompany the Squad to identify and track the target. The Squad would then stalk the prey, picking out the right moment to perform their murderous deed.

Once the target was picked and the stalking began, it was just a matter of the right moment. Often, targets had to be followed for days, with the Squad calling off their attempts multiple times as the situation was unsuitable for the job. Upon determining it was the right time to move forward, the Squad had a developed method for killing their target. One man would move up and shoot the target in the head, and the second would follow behind, unloading another shot to ensure the kill.[5] Well, at least that was their plan in theory. Unfortunately, their targets or surroundings often did not follow the wishes of the Squad, and the would-be assassins had to make changes on the fly. Their very first assignment against Detective Sergeant Smith sounds more like a gangster movie where four men ambushed the detective and unloaded their revolvers into him while he attempted to flee. Surprisingly, he survived for five days.

While the Squad’s primary role was killing, they were often involved in other assignments. Their most notorious secondary duty would be freeing prisoners from jail. In March of 1921, IRA leader John McKeon was captured in a raid and arrested. Collins determined that McKeon must be released and assigned the Squad for the rescue. Their rescue attempt was ultimately a failure, but just as sometimes their assassinations could fit into a gangster movie, this attempt would fit in any action thriller. Below is the rescue attempt step by step.[6]

- The Squad needed to steal a British armored car. They completed the theft by staking out a spot where the car regularly stopped. Four Squad Members held up the car at gunpoint on the day of the operation. They killed one soldier and held three more as hostages.

- While one group stole the car, two Squad members, Emmet Dalton and Joe Leonard, were to wait at a separate location dressed in British officer uniforms. Emmet wore his old uniform from his days serving in the British army, and Joe wore one that the IRA acquired.

- Leaving the prisoners with newly arrived Squad members, the thieves dressed in clothing similar to British soldiers and drove to the two disguised British Officers. After picking up their new passengers, the thieves went to Mountjoy Jail, where McKeon was being held.

- Once at the jail, the two “officers” requested a meeting with the governor of the jail regarding the transfer of McKeon for questioning. The IRA had sent instructions to McKeon to somehow talk his way into the governor’s office at this time so that he would be waiting for his friends. They would casually take him if things went smoothly, but if a quick escape was needed, they could grab him and run.

- Things running smoothly ended as soon as Dalton and Leonard entered the prison. First, a guard recognized Leonard from a previous stint at the jail. If you’re wondering why the Squad chose someone who had been imprisoned, the logic is twofold. First, by this point, there was not an overabundance of IRA men who had not seen the inside of a jail, and second, few in the Squad could effectively pull off a British Officer like Leonard. Even after being recognized, the men pressed forward.

- Things went from bad to worse upon reaching the governor’s office. Apparently, the day the men selected for the rescue was also the day the prison brought in new guards. This meant the guards had an extended meeting with the governor, and McKeon could not get into the office. Furthermore, the governor also recognized Leonard. Dalton and Leonard held the staff in the office at gunpoint while tying them up and fled the building.

- While Dalton and Leonard attempted to flee the prison, their comrades outside found themselves in an equally precarious position. Their attempts to secure the gate for a quick retreat had attracted the attention of a sentry, who quickly fired upon them. One Squad member, Joe Walsh, was hit in the hand, and one sentry was killed.

- Leonard, seeing what was happening, used the confusion to order the British soldiers to withdraw. It took some convincing, but they eventually listened since they did not realize he was not a British officer but rather an IRA member. From there, the Squad men hurriedly drove the armored car away from the jail. None were caught, but McKeon remained imprisoned.

While the Squad would be involved in other rescue attempts and IRA-assigned jobs, murder was their primary responsibility. Their most well-known and impactful assassinations all occurred on one day, Bloody Sunday. On the morning of Sunday, November 21, 1920, the Squad, along with help from the local Dublin IRA, forced their way into eight different locations. The result was the killing of 14 British soldiers and operatives, with an additional four wounded.[7] The number could have been higher if not for some lucky escapes and some targets surviving their wounds. Only one IRA man, Frank Teeling, was captured during this operation and later freed on Collins’ orders. The name “Bloody Sunday” does not come from just these killings. The more infamous reprisals are what helped the day earn the title. That afternoon, hundreds of people attended a game of Gaelic Football looking to watch Dublin versus Tipperary. Under their Black and Tan and Auxiliary groups, the British invaded the field and opened fire on the crowd, killing 14 people and sixty-two more.[8] Amazingly, the British suffered no injuries even though they claimed to be under fire. Bloody Sunday is one of the most important moments in the Irish War of Independence, and its impact on the eventual truce is worth evaluating on its own in a future article.

The Squad would take place in many assignments after Blood Sunday, including the daring failed rescue described above. They would follow the pattern set earlier, which consisted of a mix of efficient killings and gangland shootouts. Notably, the Squad took place in a more traditional major operation in Dublin in which they were part of a team sent to secure and destroy the Custom House, the diplomatic center for the British in Dublin. This operation differed from traditional IRA tactics of hitting quickly and fading away. They’d have to secure a building for an extended time and hold off British soldiers that arrived. The only reason this operation even happened was that Éamon de Valera, the political head of the rebels, desired the action. He was not pleased with the tactics employed by Collins. He thought they did not help the cause with the American people whose sympathy they deeply needed (some suspect he was also jealous of Collins’ influence among the army). The operation was a disaster. The British managed to get reinforcements to the area far earlier than anticipated. The building may have burned, but over eighty IRA members, including most of the Squad, were arrested, and Sean Doyle lost his life as a result.[9]

The long-term consequences of this operation were never to be truly felt. The battle occurred on May 25, 1921, and the truce with England was signed on July 11, 1921. Following the truce emerged the Anglo-Irish Treaty on December 6, 1921. The Treaty was responsible for the partition of Northern and Southern Ireland. Importantly from then on, there would be peace between Southern Ireland and Great Britain. Unfortunately, the Squad did not get to go home at this point. After their release from prison, they participated in a brutal civil war with members of the IRA who were against the Treaty. The Squad’s tactics on behalf of the pro-Treaty government were brutal. They were ruthless in their killing and torture. The entire Irish Civil War requires a complete analysis in a future article.

The Squad was a group of young men given some of the dirtiest work in a dirty war. They were the gun of IRA intelligence, removing targets deemed too dangerous to live. How you feel about their work both in the War of Independence and Civil War is a matter of personal perspective, but there is no denying they played a vital role in IRA operations. Their work helped Michael Collins get to the negotiation table with England. Their work helped lead to the Republic of Ireland.

[1] Tim Pat Coogan, The Twelve Apostles: Michael Collins, the Squad, and Ireland’s Fight for Freedom (New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016), 75-76.

[2] Coogan, 74.

[3] Piaras Béaslaí, Michael Collins: And the Making of a New Ireland, vol. 1 (Borodino Books, 1926), 294.

[4] T. Ryle Dwyer, The Squad: And the Intelligence Operations of Michael Collins (Cork, IE: Mercier Press, 2005), 92.

[5] Coogan, 119-21.

[6] Dwyer, 234-43.

[7] James Gleeson, Bloody Sunday: How Michael Collins’s Agents Assassinated Britain’s Secret Service in Dublin on November 21, 1920 (Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2004), 141-42.

[8] Gleeson, 149.

[9] Coogan, 234-37.

Leave a comment