Quick Note: As I will mention below I tried something different with this one. An investigation about an investigation. Truthfully, there is a lot to this topic so I tried to give something that had a lot of different information contained.

The Bank Act of 1933, commonly called Glass-Steagall, was one of the most significant pieces of banking legislation ever passed in the United States. It has defined banking since its inception. The most controversial portion of the bill described the relationships between commercial and investment banks. More specifically, it required a separation of the two. This portion of the bill remained controversial until its repeal in 1999. However, even today, the debate remains on whether or not that separation should resume.

The early months of 1933 were not the first time Congress debated the issue of commercial and investment banking. Senator Glass had attempted to push the issue forward numerous times before and after the start of the depression. So, what changed in 1933? Put simply, a series of congressional hearings into bank practices, commonly called the Pecora Commission, changed everything. These hearings incited the public against bankers and gave Senator Glass the environment needed to pass his separation bill.

What is more incredible is that most historians can’t agree that the Pecora Commission actually uncovered anything that justified the separation of commercial and investment banks. There was bad lending, bad investing, and fraud, but whether or not these constituted a need to separate the two divisions is questionable. So why is the Pecora Commission credited for leading to Glass-Steagall? Truthfully, the answer is public relations. The Commission caused such a stir and infuriated the public so greatly that Congress had to do something, and sitting there waiting for his time to shine was Senator Carter Glass. He had a bill ready to go, and that bill separated the two institutions. He saw a moment and seized it.

This article will be about how the Pecora Commission led to Glass-Steagall. So why do I believe that the Pecora Commission is responsible for Glass-Steagall? There are a few reasons. First, most historians agree that the Commission is the reason the act passed. Second, the timing of when the act passed. Meaning that the act failed until the Pecora Commission. Finally, by judging how much pressure the public applied to Congress because of the Pecora Commission. What will follow are my attempts at presenting a quick investigation to answer the question of was the Pecora Commission responsible for the passage of Glass-Steagall. I thought an investigation about an investigation would be interesting. Someday I might write an article about the entire Commission because it is interesting, but I was just fascinated by how public relations mattered in these years. If you are interested in the Commission, I recommend reading The Hellhound of Wall Street: How Ferdinand Pecora’s Investigation of the Great Crash Forever Changed American Finance by Michael Perino. It was one of my main references and an excellent book.

Main Players

Ferdinand Pecora was a New York City prosecutor known for his sense of justice. Though a Tammany Hall Democrat, Pecora never avoided cases that could negatively impact the party or its friends. This honesty would come to his detriment, costing him the Distract Attorney nomination[1]. However, his honesty and sense of justice would pay off. When searching for a lead investigator for their stalled investigation, the Senate Banking Committee looked towards investigators they could trust to do the job correctly. Pecora wasn’t first on their list or even originally on it, but his reputation led to his recommendation.[2] This investigation would come to define his legacy.

Senator Carter Glass was a Democrat Senator from Virginia. Born and raised during the Reconstruction era of the South, Senator Glass had a deep loathing for federal government intervention. He also detested Wall Street and believed them responsible for much of the South’s struggles.[3] This feeling would continue into adulthood and be the foundation for his politics. Senator Glass strove to limit Wall Street as much as possible. He first began with the passing of the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, which established the Federal Reserve. However, he continued to warn about Wall Street and was a staunch proponent of the separation of commercial and investment banks. He was the leading Senate figure on banking in 1933.

Though he lent his name to the Bill, Harry Steagall played a minor role in passing Glass-Steagall. A Representative from Alabama, his main contribution to the bill was authoring the section on deposit insurance.[4] Unfortunately, Steagall did not rouse the public’s anger like Pecora with his investigations or continuously press Congress and FDR to pass a bill like Glass. His contributions were so limited that he only gets mentioned in passing in all the works referencing the bill.

Investigation and Hearings

Congress had been trying to investigate banks for close to a year before they hired Pecora as their lead investigator. They had been unsuccessful in achieving any of its aims mainly due to the fact that their attorneys seemed unable to match wits with the bank heads. Furthermore, they were struggling to attract anyone of real skill and value, likely due to the short duration of the assignment. That is why they were desperate on January 23, 1933, when they called to hire Pecora. They probably didn’t realize at the time that they were fortunate to find an excellent attorney who was looking for a challenge.

Pecora was immediately put on a clock upon taking the job. Authorization for the investigation expired on March 4th. Pecora had slightly over a month to conduct his investigation and question bankers in front of Congress. By the middle of February, he was holding hearings on one bank failure, but the real game would start on February 21st when he brought in Charles Mitchell, the president of National City Bank, for questioning. He questioned Mitchell and his colleagues until March 2nd, and it was these hearings that changed everything. He exposed Mitchell for poor banking practices, fraud, and for being insanely greedy during a time when most Americans were poor and suffering.

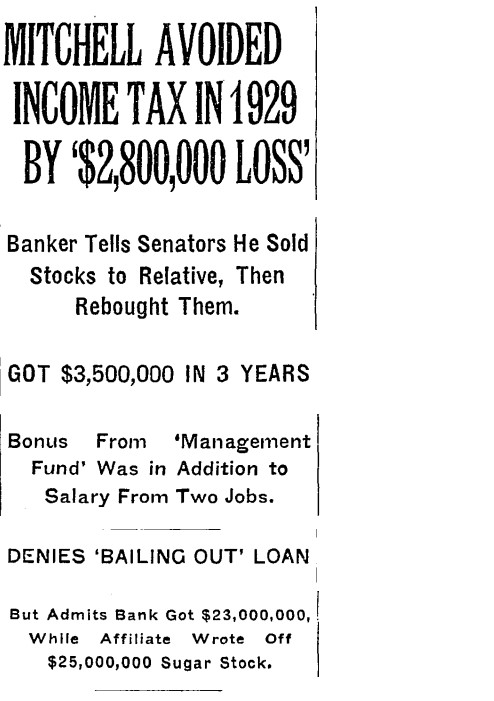

The outrage from Mitchell’s testimony granted Pecora an extension on his investigation and was the driving force behind the passage of Glass-Steagall. Several examples that came to light that fired up the public were that it was discovered that Charles Mitchell made over $3.5 million within three years. This was during a time when the average factory worker was making $17 a week.[5] There was also outrage when it was discovered that Mitchell sold and repurchased his own bank stocks to record a $2,800,000 paper loss to lower his taxes.[6] These are just two examples of the type of actions taken by bankers that Pecora leverage to continue his investigation. They also are the type that inspired anger in the public, forcing Congress to pass a bank act or risk being voted out.

Popular Opinion

So first, the investigation into the Pecora Commission’s role in the passing of Glass-Stegall should begin with the current popular opinion on the matter. So much has been written about Glass-Steagall that views on the Commission’s role are readily available. That is not to say these opinions are correct or the determining factor in answering the question, but rather, they provide insight into the matter. Moreover, these popular opinions are valuable since they had to develop out of the ideas developed at the time of passing.

In his 1990 work The Separation of Commercial and Investment Banking: The Glass-Steagall Act Revisiting and Reconsidered, George Benston has written one of the most comprehensive books on Glass-Steagall. In this book, Benston states that the damaging revelations of the Pecora Commission are one of the significant factors in the passing of Glass-Steagall.[7] Benston, throughout his book, covers several issues he has with Glass-Steagall. However, of all the problems involving Glass-Steagall Benston references in his book, Benston never debates the importance of the Pecora Commission. He may debate its actual relevancy but not its importance in passing the Act.

Susan Estabrook Kennedy wrote one of the more popular books on the Bank Act of 1933 in her 1971 book The Banking Crisis of 1933. Her work covers all aspects of the Banking Crisis from that time. It goes beyond the scope of Glass-Steagall. However, in this work, she also agrees that the Pecora Commission is a leading reason why Congress passed Glass-Steagall.

Although this separation had been central to the senator’s concept of his bill, until the spring of 1933 it had met with vigorous attack, particularly from Wall Street. The Pecora hearings changed that attitude.24 The sensational manner of these hearings, as well as their timing, on the eve of the national moratorium, inflamed public resentment.[8]

Matthew Fink wrote a biography in 2019 on Carter Glass. In his work, he agrees with previous sentiments that the Pecora Commission was a significant reason for Glass-Steagall’s passing. He describes that Carter Glass was not a fan of the investigation and may have been envious of Pecora. However, Glass saw an opportunity in Pecora’s Commission and used it for his gain.[9]

Ferdinand Pecora’s biography also supported the idea that the Commission was the reason for the passing of Glass-Steagall. In his 2010 book, Michael Perino argues that the Pecora Commission tattered bankers’ reputations tremendously. And this tattering of reputations put them in favor of Glass-Steagall in an attempt to regain their reputation. So now, instead of speaking against it, they supported it.[10]

Perino likely formed his opinion because his topic, Ferdinand Pecora, also believed he was responsible for Glass-Steagall. Ferdinand wrote a book in 1939 covering the events of the investigation. His book gives a detailed account of events as he saw them years later. In chapter 13, Pecora writes about the investigation and its impact. “Many aspects of the New Deal of course, bore no direct relation to the subject matter of the Senate Committee’s inquiry. But four statures, in particular, grew out of the effort to cope with the abuses it had revealed.”[11]

It was not just works written years after Glass-Steagall’s passage that held the belief that the Pecora Commission influenced things. For example, in the Journal of Political Economy in December of 1933, Ray Westerfield describes a changing atmosphere surrounding Glass-Steagall. He references the Senate hearings revealing the bad practices of banks. He said this and bank losses changed the debate from whether separation should happen to how long banks should have to separate.[12] This article was an opinion of a writer at the time of Glass-Steagall. It’s a good example that people believed Pecora to be the reason for Glass-Steagall.

This section included the works of 4 well-respected writers on Glass-Steagall, written by Pecora himself, and an article from the time of passing. All agreed that the Pecora Commission was responsible for the passing of Glass-Steagall. These writings range from 1939 to 2019. This range in time shows that the popular belief that the Commission is responsible for Glass-Steagall has been around since nearly the inception of the Act. While this does not answer the question, it at least is something to consider when evaluating all the facts.

Timing

When evaluating the Pecora Commission’s role in the passing of Glass-Steagall, no one can ignore the issue of timing. All works that mention Pecora and Glass-Steagall also note that Glass-Steagall could not get passed before Pecora. The assumption being, of course, that since Congress passed Glass-Steagall after Pecora, they did so because of Pecora. This section will evaluate the merit of the timing argument. Specifically, does the timing of Glass-Steagall’s passing truly reflect Pecora’s importance, or is everyone making a bad judgment?

The first step in this evaluation is establishing that the Pecora Commission did not discover the issues within commercial and investment banking. Senator Glass had long held the belief that there were issues between the intermingling of commercial and investment banks. By 1932, Senator Glass and his subcommittee had fully embraced the idea that Congress must pass a regulation separating the two.[13] He put up his original bill requiring the separation in 1932.

Furthermore, debates were already taking place within Congress by 1932. During the 1st session of Congress in 1932, Senator Costigan referenced a Washington Herald article speaking of the intertwining of commercial and investment bank practices. Senator Costigan states that he believes these practices have led to great offenses. Therefore, he was in favor of a deeper investigation.[14]

While the previous paragraphs show that Pecora did not discover new information, they also reveal a crucial fact. That being that Congress knew the issues and passed nothing. Congress continued to shelve Glass’s bill, which he first proposed in 1932. They were willing to have debates but did not pass anything.

The only major events between Glass’s original proposal and Glass-Steagall’s passing were the inauguration of FDR and the Pecora Commission. A new president’s election would seem like a good case for explaining shelved legislation now being passed; however, FDR’s election does not seem to work in this scenario. While banking was a significant concern of FDR, the idea that Congress needed to separate commercial and investment banks was not on his agenda. His first fireside chat dealt more with restoring consumers’ confidence in banks than bankers’ sins.[15] FDR does not fit as a good reason.

Eliminating FDR’s election leaves the Pecora Commission as the only major event. The Pecora Commission dealt directly with the intermingling of commercial and investment banks. Pecora took a strong stance against the intertwining. “A prolific source of evil has been the affiliated investment companies of large commercial banks.”[16] Meaning that a major Commission was getting attention and proclaiming the evils of commercial investment banks. Timing does seem to favor the argument in favor of the Pecora Commission.

Pecora Commission’s Impact

So how would the Commission lead to Glass-Steagall? The first method would be to uncover new information leading to the government stepping in. However, as previously discussed, Congress already knew about most of the issues presented by the Commission. That leads to the second way the Commission could lead to Glass-Steagall, which is public pressure. The Pecora Commission could get so much negative attention on the issues that Congress has to pass legislation. Public pressure forcing Congress to act is what happened with the Pecora Commission.

Measuring public pressure is not easy. There is no meter monitoring the pressure the public is applying. The only way possible is to take a survey of publications from around the time and judge if they are moving forward with the narrative of the Pecora Commission. It is also essential to check Congressional records regarding Pecora. Was he mentioned? Were the hearings mentioned? These questions will gauge impact. It should be noted that the Pecora Commission is often referred to as just the Senate hearings in publications.

Publications referencing the Pecora Commission or Senate hearings were not difficult to find. For example, the New York Times ran many stories in 1933 during the time of the Pecora Commission and Glass-Steagall. A simple search of records will show a large number of articles published. They range in nature from the simple reporting that the investigation will continue to the more aggressive reporting of the misdeeds committed by bankers.[17] The New York Times was a major publication, and its focus on the investigation would catch the public’s attention.

It was not just the New York Times publishing articles about the Senate hearings. Well-known journalist John T. Flynn wrote several works on the topic. In one of his articles for The New Republic, Flynn rails against investment bankers. He shows great disdain for the damage he believes they have done. However, he also is adamant that something has to happen now and not down the road.[18] This article is a perfect example of the pressure writers put on Congress aided by the revelations of the Pecora Commission.

J. M. Daiger’s writing in Current History was a good summation of the current feelings of the public. In this article written in February of 1933, Daiger covers Senator Glass’s struggles over the last several years to get his proposed legislation passed. Daiger continues that things seemed to have changed, and he attributes this to a more negative view of banks in the public’s eye. The investigation and revelations were game-changers, and Daiger now believes Glass can get his bill through Congress.[19]

These are some of the articles written during 1933 as the Commission was operating and Glass-Steagall was on the Congress floor. There are more, but it would become repetitive to show them all. They show that there was pressure on Congress to do something. Now it is time to reflect on whether Congress noticed.

Reading any of the Congressional records from 1933, it becomes obvious Pecora’s investigation is not going unnoticed. Pressure from newspapers is also evident as members of Congress frequently reference articles. For example, during the Senate session on May 24, 1933, Senator Patman throws his support behind Pecora while referencing a newspaper that accuses Pecora of being too easy on bankers.[20]

Senator Vandenberg provides a second example of newspapers influencing Congress when on June 8, 1933, he quotes directly from the Washington Star. The quotes cover the various aspects of the Bank Act, but it specifically mentions that the Senators act with justice when they separate commercial and investment banks.[21] It is very clear that Congress was aware of what the public desired.

Conclusion

Looking at all the facts, the answer to the question becomes more apparent. The Pecora Commission led to public outrage, which made its way to the steps of Congress. This outrage forced Congress to vote in favor of a bill they previously had ignored. Therefore, the Pecora Commission led to the passage of Glass-Steagall.

This conclusion is fascinating because it shows the power of public perception. Pecora did not present new ideas to Congress. They had long felt there was an issue regarding the relationship between commercial and investment banks, but they did not intend to do anything about it. It took a public relations disaster for banks to get Congress to do anything. It really shows the power of the public when focused.

I hope this was a fun way to learn about a historical topic. I thought I would try something a bit different.

[1] Michael A. Perino, The Hellhound of Wall Street: How Ferdinand Pecora’s Investigation of the Great Crash Forever Changed American Finance (New York: Penguin Press, 2010), 42-43.

[2] Ibid, 59

[3] Matthew P. Fink, The Unlikely Reformer: Carter Glass and Financial Regulation (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 2019), 4-9.

[4] George J. Benston, The Separation of Commercial and Investment Banking: The Glass-Steagall Act Revisited and Reconsidered (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 1.

[5] Perino, 147

[6] “Mitchell Avoided Income Tax in 1929 by ‘$2,800,000 Losds’,” New York Times (1923-) (New York, N.Y.), 02/22/

[7] Benston, 215

[8] Susan Estabrook Kennedy, The Banking Crisis of 1933 (University Press of Kentucky, 1973), 212.

[9] Fink, 110-11.

[10] Perino, 289.

[11] Ferdinand Pecora, Wall Street under Oath: The Story of Our Modern Money Changers (NY: Graymalkin Media, 2014. First Published 1939 by Simon and Schuster).

[12] Ray B. Westerfield, “The Banking Act of 1933,” Journal of Political Economy 41, no. 6 (1933): 738-39.

[13] Fink, 85-95.

[14] Cong. Rec., 72nd Cong., 1st sess., 1932, Vol. 75, pt. 5:5433.

[15] Amos Kiewe, FDR’s First Fireside Chat: Public Confidence and the Banking Crisis (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2007), 96.

[16] US Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, The Pecora Commission’s Final Report, (Washington, DC, 1934), 113

[17] “Financial Inquiry Slated to Continue: Enabling Resolution Introduced in the Senate Is Expected to Receive Approval. Whitney Next on Stand Stock Exchange Head Will Be Heard Tomorrow — Mitchell Gets Testimony. Medalie Pursues Quiz Wheeler and Simpson, on Radio, Denounce Insult and National City Bank Tactict,” New York Times (1923-) (New York, N.Y.), February 26, 1933, https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/financial-inquiry-slated-continue/docview/100755852/se-2?accountid=12085.;

[18] John T. Flynn, “The Bankers and the Crisis,” Article, New Republic 74, no. 955 (March 1933): 157-59.

[19] J. M. Daiger, “Toward Safer and Stronger Banks,” Current History (1916-1940) 37, no. 5 (1933): 558-64.

[20] Cong. Rec., 73rd Cong., 1st sess., 1933, Vol. 77, pt. 4:4122.

[21] Cong. Rec., 73rd Cong., 1st sess., 1933, Vol. 77, pt. 6:5255-5256.

Leave a comment