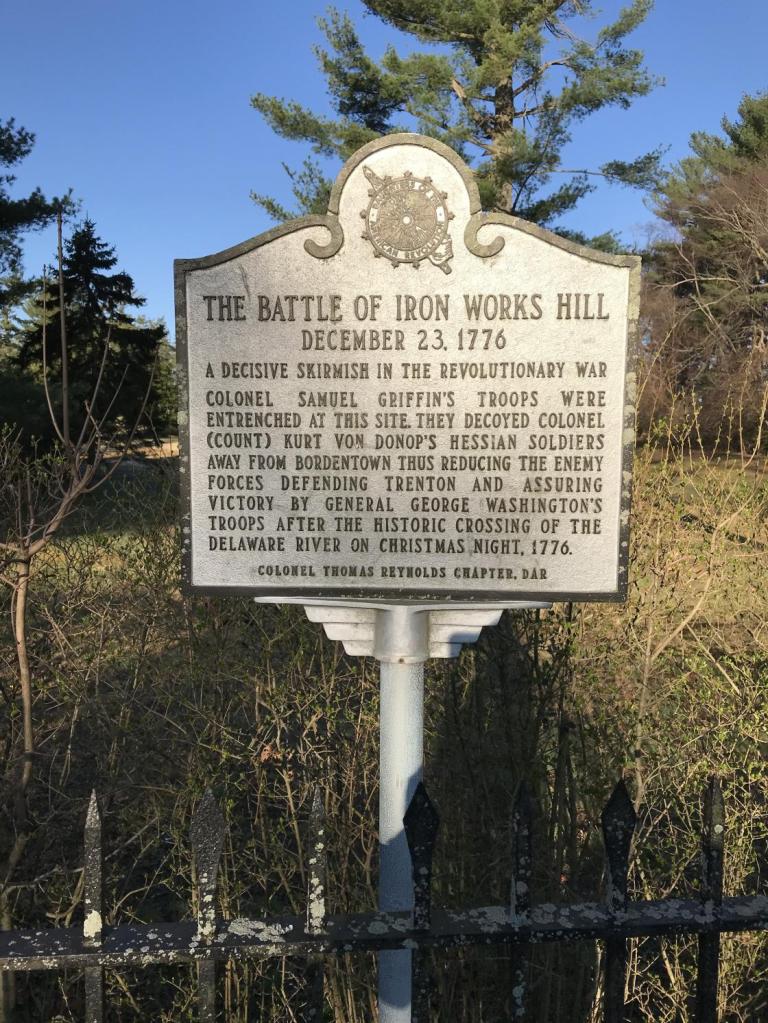

I was looking for smaller and less monumental battles of the American Revolution. The type that was important but unrecognized. Searching through battles all over the colonies, I came upon a small series of skirmishes in New Jersey that played a part in a much big victory. The battle took place in and around the town of Mount Holly, New Jersey. The battle would become known as the Battle of Iron Works Hill. On December 22nd and 23rd in 1776, colonial militia fought a series of skirmishes with the intention of drawing Hessian Soldiers away from their encampment in Trenton, NJ. Mount Holly’s historical supporters believe this battle played a crucial role in the success of the Battle of Trenton. They claim that drawing troops away from Trenton gave Washington the ability to succeed.

At the start of the Revolution, Mount Holly sat as a town mixed with loyalists, patriots, and pacifists. It was close to the central hub for the Revolution, Philadelphia, but was far enough away that it seemed like it would be kept from playing any role in the conflict. The people of Mount Holly were unaware that their town would have a small but significant part in the war. For two days in December 1776, Mount Holly never mattered more.

While Mount Holly waited to play its part, the American forces were in trouble. George Washington had just suffered several defeats in New York, climaxing with the losses at Forts Washington and Lee in November 1776. Washington found himself being chased through New Jersey by General Cornwallis. The outlook was bleak for the young, inexperienced army.

As the colonies waited for Washington to plan his next move, Mount Holly had an inauspicious start to its place in Revolutionary history. On December 12, 1776, colonial forces arrested Dr. Daniel Bancroft in Mount Holly for being a spy. In his appeal to the Continental Congress, Bancroft tells the tale of being forced to an oath to the Hessians “to not take up arms in the present war.” He went on to state that this oath was taken for his personal safety, and he was not against the liberty of America.[1] He was released in April of 1777 and went on to become a surgeon for Loyalist forces.

In December of 1776, George Washington planned his daring raid on Trenton. After spying on the enemy in Trenton, as reported by Hessian Adjutant General Major Baurmeister, Washington felt he knew what he must do.[2] He planned to lead his forces of 2,400 men across the Delaware River against the 1,500 Hessian soldiers led by Colonel Johann Rall.[3] He issued his general orders on December 25,1776.[4] Unfortunately, Washington’s forces would not receive reinforcements as planned when two detachments could not make the crossing of the river. Washington was aware that there were an additional 2,000 Hessian soldiers in South Jersey under Colonel von Donop. These troops had to stay away from Trenton.

George Washington turned to Colonel Samuel Griffin to lead a force of about 600 men against Colonel von Donop. The sole goal was to keep Von Donop’s forces far enough below Trenton so as to be unable to render aid to Colonel Rall. Griffin’s strategy was simple attack and retreat. He was not looking to win a great victory. He sought only to distract. Griffin’s plan is recorded in the Journal of General Joseph Reed, who served as Adjutant-General to the Continental Army. Reed records that Griffin’s forces would be unable to render any service beyond drawing the attention of the Hessian forces.[5]

First-person accounts of the battle are limited. The best account is from Hessian Captain Johann Ewald. His journals report on the numerous skirmishes that occurred on those two days in December. His report describes how the colonial militia would strike and then retreat. This kept the Hessians constantly chasing for engagement. Ewald even records the reception of the news that Washington had attacked Trenton.[6]

The only real account of the skirmishes occurring in South Jersey from an American comes from the journal of George Ewing. George was a soldier in the New Jersey militia. He served at Brandywine and Germantown, and he spent the winter at Valley Forge. His journal reports several days of clashes with both militia advances and retreats.[7] While the information contained is scarce, the fact that it is the only colonial first-hand account available is significant.

As mentioned, there is a lack of primary sources on the colonial side regarding the skirmishes, but there are accounts of citizens living in the area at the time. For example, John Hunt was a local Quaker living in Moorestown who reported in his journal about the days leading up to the skirmish. He states that on the 15th of December, the town is concerned about the British moving in and that residents may try to hide. However, he continues that a skirmish between Americans and Hessian forces on the 22nd ended with the Americans retreating and the Hessians remaining in Mount Holly. [8]

Joseph Galloway was a loyalist living in South Jersey at the time of the battles. He wrote Letters to a Nobleman: On the Conduct of the War in the Middle Colonies in 1779, in which he reports what he saw from those days and his opinions on what occurred. Galloway did not respect the Hessian commanders accusing Rall of being drunk. He confirms other accounts of militia attacking and retreating.[9] His account is interesting in both his support of England and his dislike of Hessians.

Margaret Morris’ Revolutionary journal is one of the more well-known documents from that time in South Jersey. She lived in Burlington, NJ, and reported all she heard during the Revolution. She covers the days leading up to the skirmishes, giving the reader insight into the fear and anxiety gripping the area. Finally, she talks about the Hessians routing the colonial troops at Mount Holly. It should be noted when referring to colonial troops, Margaret uses the term “we” to show her allegiance.[10] Margaret’s account may be the least accurate on the actual battle, but it provides the best resource for the emotions of the time.

There were some newspaper accounts of the battles. The Pennsylvania Evening Post reported on December 24th that the conflicts had occurred. It notes that Colonel Griffin led the colonial militia. It also provides casualties reports of two killed and seven or eight wounded. It also stated that the enemy had several killed and wounded. This source is unique because it is a newspaper and provides casualty numbers.[11]

Finally, Robert Morris, a congressional delegate, wrote to John Hancock about Washington’s Trenton plan. As part of this letter, Morris covers the battles in Mount Holly. He explains to Hancock the plan to have Griffin’s militia forces pull Hessians away from Trenton. An interesting point regarding this letter is that it is dated December 26, 1776, a day after the battle.[12] This date results from the slower mail system, but it is interesting.

The Battle of Trenton was a great success for the American forces. It provided a much-needed morale boost to an army on its heels. So, did the skirmishes in and around Mount Holly help with the battle? Unfortunately, the letter from Washington to Griffin on December 24, 1776, does not mention the fights Griffin just led but instead discusses issues with the army.[13] However, a letter dated December 27, 1776, to John Hancock helps shed some light on the situation. In his letter, Washington addresses His Generals’ inability to bring their troops to Trenton. Washington states:

“I am fully confident, that, could the troops under Generals Ewing and Cadwalader have passed the river, I should have been able with their assistance to drive the enemy from all their posts below Trenton. But the numbers I had with me being inferior to theirs below me, and a strong battalion of light infantry being at Princeton above me, I thought it most prudent to return the same evening with the prisoners and the artillery we had taken.”[14]

Washington expressly states that the size of the opposing forces helped dictate the battle. If Washington needed greater forces for great success, it is likely that the Hessians having an additional 2,000 troops would have led to defeat. Washington needed as few Hessians in Trenton as possible in order to win his victory. The Hessians were kept away from Trenton due to the actions of the militia in Mount Holly.

It has to be mentioned that there is a good chance that a citizen of Mount Holly played the most crucial role in the entire affair. In 1979, Johann von Ewald’s journals were discovered. In these journals, Ewald states that von Donop stayed in Mount Holly because he had “found in his quarters the exceedingly beautiful young widow of a doctor.”[15] In an ironic twist of fate, Historians Dennis Rizzo and Alicia McShulkis believed the “widow” to be the wife of Dr. Daniel Bancroft, whom the Americans were holding as a traitor.[16]

The aftermath of the battle between the British and the Americans would take an entire book to explain. Instead, this section focuses on some of the key players and Mount Holly. Colonel Rall, the commander of the Hessian Troops in Trenton, was mortally wounded in the battle. He died on December 27, 1776. George Washington went on to lead the Americans to victory in the Revolution and served as the nation’s first President after the constitution’s ratification.

The leader of the Hessian forces in Mount Holly, Colonel von Donop, continued to serve in the Hessian troops until he was killed in the Battle of Red Bank in 1777. Colonel Samuel Griffin’s story is a bit unique in that he appears to step out of the war after the battle, but there is no clear understanding as to why. He wrote a letter to George Washington on January 30, 1777, apologizing for his continued illness.[17] Furthermore, a letter from Washington to Joseph Reed dated February 23, 1777, states that Griffin has turned down several promotions.[18] It is possible Griffin wanted more recognition, as hinted at in the letter from Washington to Reed, or it is possible he needed to step back for his health. He lived until 1810.

The Hessians pulled out of Mount Holly shortly after the Battle of Iron Works Hill, and British forces stayed away from Mount Holly until 1778. However, American forces were around Mount Holly frequently during those years. In April of 1778, George Washington received notification of a court martial occurring in Mount Holly. William Leeds was being accused of desertion.[19] Furthermore, the colonial government exerted power by holding Court of Admiralty sessions in Mount Holly. Typically these would take place in someone’s home.[20]

The British reoccupied Mount Holly in June of 1778. They retreated to the New Jersey area after leaving Philadelphia. In an ironic twist, the British also held a court-martial in Mount Holly. British orders from the time mention the court-martial, but they do not say who is being accused and for what. They also give an account of the British leaving Mount Holly on June 22, 1778.[21] It is a fun thing to note that as soon as the British moved out, the Admiralty Courts began once again. No time was wasted in reestablishing authority. They would continue over the next several years, as seen in newspapers from the time.[22]

[1] Daniel Bancroft to the Committee of Congress, January 10, 1777, “Supreme Executive Council Clemency File (Roll 723)”, Clemency File, 1775-1790, undated, 1775, 218-224 https://digitalarchives.powerlibrary.org/psa/islandora/object/psa%3A1894131.

[2] Carl Leopold Baurmeister, Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, ed. Bernhard A. Ulendorf (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957), 75. https://archive.org/details/revolutioninamer00baur/page/n3/mode/2up.

[3] George Washington to John Hancock, December 27, 1776, The Writings of George Washington (New York: G.P. Putnam’ Sons, 1889). https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/ford-the-writings-of-george-washington-vol-v-1776-1777

[4] “General Orders, 25 December 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0341. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 7, 21 October 1776–5 January 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997, 434–438.

[5] Joseph Reed, “General Joseph Reed’s Narrative of the Movements of the American Army in the Neighborhood of Trenton in the Winter of 1776-77,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 8, no. 4 (1884): 392, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20084674.

[6] Johann von Ewald, Diary of the American War : A Hessian Journal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 35-42.

[7] George Ewing, William Cox Ewing, and Thomas Ewing, George Ewing, Gentleman, a Soldier of Valley Forge, ed. Thomas Ewing (Yonkers, NY: Thomas Ewing, 1928), 13-15. https://archive.org/details/georgeewinggentl00ewin/page/n7/mode/2up.

[8] John Hunt, John Hunt Journal, 1776 12mo. 24 – 1787 12mo. 22, John Hunt Papers, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College https://ds-pages.swarthmore.edu/friendly-networks/journals/sc203241

[9] Joseph Galloway, Letters to a Nobleman: On the Conduct of the War in the Middle Colonies, London: Printed for J. Wilkie, No. 71, St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1779, 51-55. https://archive.org/details/letterstonoblema00gall/page/52/mode/2up?view=theater

[10] “Revolutionary Journal of Margaret Morris of Burlington, New Jersey, Ii,” Bulletin of Friends’ Historical Society of Philadelphia 9, no. 2 (1919): 65-72, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41945472.

[11] Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey ed. William S Stryker, vol. 1. 1776-1777 (Trenton, NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Co., Printers, 1901), 242-43. https://archive.org/details/ser2newjerseyrev01newjuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater.

[12] Robert Morris to John Hancock, December 26, 1776, in Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, ed Paul H. Smith (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976-2000)

[13] George Washington to Samuel Griffin, December 24, 1776, in Founders Online, National Archives, Original Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol 7, 21, October 1776-5 January 1777, ed Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 428-429. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0355

[14] George Washington to John Hancock, December 27, 1776, The Writings of George Washington (New York: G.P. Putnam’ Sons, 1889). https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/ford-the-writings-of-george-washington-vol-v-1776-1777

[15] Ewald, 42.

[16] Dennis C. Rizzo, and Alicia McShulkis, “The Widow Who Saved a Revolution,” Garden State Legacy (2012), https://gardenstatelegacy.com/files/The_Widow_Who_Saved_a_Revolution_Rizzo_McShulkis_GSL18.pdf.

[17] Samuel Griffin to George Washington, January 30, 1777, in Founders Online, National Archives, Original Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol 8, 6, January 1777-27 March 1777, ed Frank E. Grizzard, Jr (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 187-188.

[18] George Washington to Joseph Reed, February 23, 1777, The Writings of George Washington (New York: G.P. Putnam’ Sons, 1889). https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/ford-the-writings-of-george-washington-vol-v-1776-1777

[19] George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Army Court Martial, April 8, Proceedings at Mount Holly, New Jersey. April 8, 1778. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw450243/.

[20] Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey ed. Francis B. Lee, vol. II, 1778 (Trenton, NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Co., Printers, 1903), 217. https://archive.org/details/ser2newjerseyrev02newjuoft/page/216/mode/2up.

[21] The Kemble Papers, vol. 1, 1773-1789 (New York, New York: New-York Historical Society, 1883), 596-97.

[22] Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey ed. Austin Scott, vol. V, October, 1780-July, 1782 (Trenton, NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Co., Printers, 1917), 38. https://archive.org/details/ser2newjerseyrev05newjuoft/page/38/mode/2up?view=theater.

Leave a comment